Elyse Kopecky started running competitively at age 12—and didn’t get her period regularly until age 30. Meghann Anderson-Russell spent two years trying to get hers back after she ramped up her running routine to lose weight. And Megan Flanagan, a track and and cross-country runner who graduated from the University of Minnesota and cofounder of Strong Runner Chicks, has been dealing with menstrual irregularities since her junior year in high school.

So while many people expressed shock back in 2017 when elite marathoner Tina Muir announced she was stepping away from running after nine years of amenorrhea—or lack of periods—these women felt a pang of recognition.

Kopecky recalls her embarrassment about the issue in high school. “My mom took me to my first gynecologist appointment and they said, ‘Well, we need to do an ultrasound to make sure she has a uterus,’” she says. “And I was completely freaked out by the idea of having an ultrasound at 16. To me, that was only what pregnant women did.” In college at the University of North Carolina, she went on birth control specifically to regulate her period—common practice at the time.

More From Runner's World

While she did appear to get a cycle thanks to oral contraceptives, experts now know menstrual irregularities in runners usually stem from a mismatch between the energy they take in and how much they expend, and that oral hormones only mask the underlying issues. It’s a concept retired elite runner Lauren Fleshman alludes to in another recent viral post, a letter to her younger self: “If you get to the dips and valleys and fight your body, starve your body, attempt to outsmart it, you will suffer. You will lose your period. You will get faster at first. And then you will get injured.”

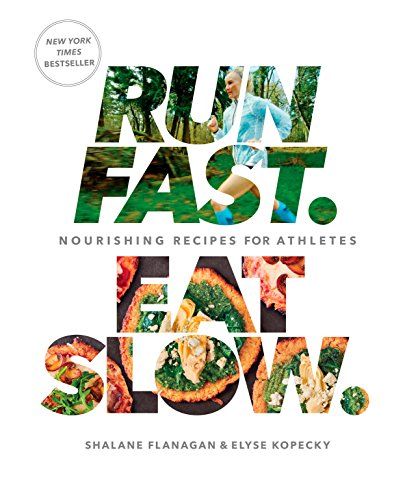

Eventually, Kopecky moved to Switzerland and traded her seemingly healthy low-fat diet for local fare consisting of whole, high-fat foods. After two months, her period returned—a transformation that inspired her to become a nutrition coach and write the bestselling Run Fast, Eat Slow cookbook with elite marathoner Shalane Flanagan.

Here’s what runners need to know about irregular periods and what to do if your cycle gets wonky. The good news: You won’t necessarily have to stop running, says sports endocrinologist Kathryn Ackerman, M.D., M.P.H., medical director of the Female Athlete Program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

For the latest training tips and health advice, join Runner’s World+ today!

How does running affect your period?

Your body requires a certain amount of calories—energy—to keep all its basic systems humming along smoothly. Each mile you cover burns a significant amount, so if you’re not careful about your fueling, you can easily run a deficit, says Laura Moretti, M.S., R.D., a sports dietitian at Boston Children’s Hospital.

This energy deficiency triggers a cascade of hormonal effects. Your body suppresses the sex hormone estradiol, and with it, the whole line of communication between your brain and reproductive organs that precipitates your period. Your tissues also stop responding to human growth hormone, a compound that makes your muscles and bones stronger. Your thyroid doesn’t function as well, slowing your metabolism. Meanwhile, your levels of the stress hormone cortisol—which can break down muscle—soar.

“This is basically the body’s way of trying to bring up energy reserves so that the athlete can address the immediate stress,” says Adam Tenforde, M.D., director of running medicine at the Spaulding National Running Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “But being in that state for long periods of time can be disruptive to overall health.”

Irregular periods make up one part of a condition traditionally called the female athlete triad, which also includes poor nutrition and weak bones. In many cases, disordered eating is at play—though in others, athletes may simply not realize how much energy they require, says Jennifer Carlson, M.D., who studies and treats amenorrhea and the triad at Stanford University.

How common is amenorrhea?

Amenorrhea and other components of the triad frequently occur in rowers, dancers, gymnasts, and weightlifters, among others. Statistics are hard to come by—some suggest more than half of female athletes have experienced amenorrhea, says Catherine Gordon, M.D., chief of the Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, and lead author of updated guidelines for treating the condition released in 2017 by The Endocrine Society. One study of high school athletes found more than three-fourths had at least one component of the triad.

One thing that is clear: The issue isn’t limited to elite or professional athletes. Tampa-based Anderson-Russell started running in her early 20s to lose weight and says she topped out at around 40 miles a week when she stopped getting her period. “I’d gone from somebody who was super sedentary and didn’t do anything, and then all of a sudden, I was running 3 miles a day and building from there,” she says. “I realized eventually that my body didn't have time to catch up with it.”

Is it dangerous to not have a period for months?

At first, losing them might seem like a blessing. After all, who wants to worry about pads or tampons during long runs or races? But with menstruation comes an assurance that your body’s basic systems are working properly. Consider it a sort of monitoring system for how well you’re handling your training load, Tenforde says.

One of the most thoroughly studied, serious, and long-term effects has to do with bone health. Women’s bodies reach peak bone mass by age 18 to 20, but even afterward, your body continues to break down and rebuild bone. If you don’t have a period, you likely don’t have the raw materials to do so, and you’re missing out on bone-protecting estrogen as well.

So, you stand a greater risk for osteopenia, osteoporosis, and stress fractures, especially in areas such as your pelvis, back, and heel-bone, according to a study published 2016 in The American Journal of Sports Medicine. Kopecky fractured her growth plates in high school and sustained two stress fractures in college; testing afterward revealed low bone density.

Beyond weak bones, your immune system might not work properly, making you sick more often. Anemia or thyroid problems can leave you feeling sluggish and cause your weight to increase even as you eat less. And though more research is needed to truly understand the links, the poor response to growth hormone and increased cortisol levels likely increase the risk of muscle strains and other injuries as well, Tenforde says.

As a result, your heart rate and blood pressure may drop dangerously low—Carlson has seen athletes with resting heart rates in the 20s (normal is 50 to 60 for well-trained athletes, 60 to 100 for the general population). Add in an electrolyte imbalance, common with poor nutrition, at you’re at risk for potentially deadly heart rhythm problems and cardiac events.

Additionally, a 2019 study published in the American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology found that not getting your period for an elongated amount of time can lead to an estrogen deficiency, which in turn can increase cause your blood vessels to not function properly and increase your LDL (or bad) cholesterol levels.

In a powerful post on Strong Runner Chicks, Flanagan (no relation to Shalane) writes that at her lowest point, she limited herself to 1,500 to 1,700 calories per day in an attempt to get lighter and faster. Instead, she lost her period and felt exhausted, confused, and achy. Her weight and race times stagnated. She’s since worked with a dietitian and physician, adjusted her mindset to view food as fuel, and embraced a heavier, healthier weight. Still, her period hasn’t returned regularly, she says.

Can amenorrhea affect fertility?

Though she’s not ready for kids yet, Flanagan does worry about her future family—a common concern among athletes with amenorrhea. While irregular periods can pose a challenge to getting pregnant, there’s no evidence skipped periods earlier in life mean you won’t be able to conceive later, Ackerman says.

Cases in point: Kopecky has two children. Both times, she got pregnant within a month of trying, she says. And though Anderson-Russell did spend longer trying to conceive and had one miscarriage, she now has a daughter.

“The reason some people who have triad are infertile is usually because they haven’t changed their behaviors,” Ackerman says. “But when I’ve had patients who are all in, they have a goal of trying to get healthy and get their cycle back, they usually do pretty well.”

When should you seek medical attention?

That doesn’t mean you should wait until you’re ready to procreate to address irregular periods, Ackerman cautions. Correcting energy deficiencies early can reduce the risk of fractures, weak bones, and other health complications down the line.

Tenforde advises any young athlete who hasn’t started her period by age 15 to visit a doctor. For adults who’ve been regular in the past, three months without a period warrants evaluation, Carlson says.

Look for someone who’s experienced in the treatment of athletes, she recommends. If a health care provider tells you irregular periods don’t matter that much, encourages you to go on birth control, or tells you to stop running without doing a thorough assessment of your diet and exercise habits, you’ll probably want to seek another opinion.

Why don’t doctors recommend birth control the way they once did? The “period” you get when taking oral contraceptives is a result of withdrawal from hormones—a false reassurance that can mask the true underlying problem, Gordon says. Your body breaks down oral hormones differently, and they don’t have the same benefits for your bones—in fact, they might even inhibit your body’s bone-rebuilding cells, called osteoblasts. Finally, there’s evidence your body produces less estrogen on its own while you’re taking them, another hit on your bone and hormonal health, Tenforde says.

How can you get your cycle back?

First things first: You won’t automatically have to stop running. “If somebody’s medically stable—if their heart rate, blood pressure, and other signs are looking OK—I will not necessarily back off on their activity as their first recommendation,” Carlson says. “For a lot of athletes, taking that away is a really big deal.” Collegiate runners can lose scholarships, and runners of any age or level might lose their motivation or feel stressed out—a situation that, by raising cortisol levels, actually can further contribute to menstrual irregularities, Ackerman says.

Your doc will likely run tests to rule out other medical causes of abnormal periods, including tumors, genetic abnormalities, and a hormonal disorder called polycystic ovarian syndrome or PCOS. But energy deficiency is “far and away” the biggest cause of menstrual irregularities in athletes, Carlson says.

The Endocrine Society guidelines recommend a treatment team consisting of an endocrinologist, dietitian, and a psychologist or psychiatrist, who can assist with behavior change, treat any disordered eating, and provide help managing stress levels. In fact, a small study in the journal Fertility and Sterility found cognitive behavioral therapy alone could restore periods in some women.

Most athletes, however, require diet shifts to restore their energy balance. In some cases it’s purely a matter of quantity, Moretti says. Other runners need to rebalance their ratios of macronutrients, often boosting their intake of carbohydrates (which provide quick fuel) or healthy fats (which carry nutrients and help your body manufacture hormones). The right ratio depends on an athlete’s individual physiology and where she’s at in the training cycle, Moretti says, and a dietitian can help her get it just right.

[Smash your goals with a Runner’s World Training Plan, designed for any speed and any distance.]

How long does recovery take?

The process of getting your period back can take anywhere from a few weeks to six months, Carlson says. In the meantime, your doctor can monitor levels of estrogen and other hormones to make sure you’re moving in the right direction.

Sometimes, the process does involve weight gain. Fat tissue produces estrogen, so some is essential for healthy menstruation, Gordon says. However, the exact percentage required likely varies from person to person. For Kopecky, miles of trail running in Bend, Oregon, got her back to her college weight before her second pregnancy, with no further disruption in her periods.

Anderson-Russell says she gained about five pounds in pursuit of her period but recognizes it was weight she probably needed. Despite the myth that leaner is always faster, it’s likely an athlete who does gain weight to restore her period will perform better at a healthier weight and all systems working properly, Ackerman says.

Cutting back or quitting exercise altogether might move the process along more quickly, provided it doesn’t add stress, Ackerman notes. And in some cases, such as in people with life-threatening eating disorders, it’s absolutely necessary. However, many athletes—including Kopecky and Anderson-Russell, who trained and completed an Ironman after getting her period back with a higher-calorie diet—have been able to continue the sport they love as they regained their cycles.

Though it may feel difficult to discuss at times, experts and runners say they’re grateful to Muir for bringing the issue to light and breaking through the stigma and shame surrounding it. Flanagan, for one, says she feels newly motivated to explore her options and take action.

“I guess for me the next step is meeting with another doctor and maybe checking hormone levels and seeing what it could be,” she says. “I’m still kind of in the early stages of figuring it all out.”

Editor’s note: This article has been corrected to reflect that a common resting heart rate for well-trained athletes is 50 to 60 beats per minute.

Cindy is a freelance health and fitness writer, author, and podcaster who’s contributed regularly to Runner’s World since 2013. She’s the coauthor of both Breakthrough Women’s Running: Dream Big and Train Smart and Rebound: Train Your Mind to Bounce Back Stronger from Sports Injuries, a book about the psychology of sports injury from Bloomsbury Sport. Cindy specializes in covering injury prevention and recovery, everyday athletes accomplishing extraordinary things, and the active community in her beloved Chicago, where winter forges deep bonds between those brave enough to train through it.