At some point, if you’ve been running for a while, you eventually just need sometime off from the sport. And there’s nothing wrong with taking a break from running. Sometimes you need a pause to heal an injury or recover from a grueling training cycle. Other times, you need to take a step back from constantly stepping forward to help your mental health. So, how do you start running again after a break?

When it comes time to lace up after a hiatus—no matter the reason you put a pause on your workouts—how exactly you start running again comes down to a few key strategies. And following those strategies will help you not only build up your mileage and your fitness, but also give you a confidence boost so you can keep the good times running.

Here, everything you need to know about making a running comeback and setting yourself up for success as you ease back into the sport.

More From Runner's World

1. Recognize Changes to Your Fitness

A few key things happen to the body when you stop running: There’s a decrease in blood volume and mitochondria (the power plants in our cells), plus your lactate threshold falls, says coach and exercise physiologist Susan Paul.

However, the longer you have been training, the more quickly you’ll be able to get back into it after a layoff, she says. So, in general, someone who has been running consistently for 15 years, then takes a year-long break, will have an easier time returning to running than someone who has been running for one year, then is off for a year.

The reason? The longer you’ve been running, the stronger your aerobic base, says Paul. You’ll have a much higher level of mitochondria to produce energy, more red blood cells to deliver oxygen to the running muscles, and more metabolic enzymes to push you through your run, compared to someone who just started working out.

So while your fitness falls during a layoff, it won’t fall as low as if you had just begun running because you’re already starting at a much higher fitness level. In general, here’s how much of your maximal aerobic capacity (a.k.a. your VO2 max)—or cardiorespiratory fitness—you may lose with time off, according to Paul:

- 2 weeks off: lose 5–7 percent of VO2max

- 2 months off: lose 20 percent of VO2max

- 3 months off: lose 25–30 percent of VO2max

Also, keep in mind you do lose strength and power in your muscles, tendons, ligaments, and connective tissues. It’s difficult to assess how much conditioning you lose, or how quickly you lose it. But it’s the weakness in the musculoskeletal system that causes so many people to get injured when they return to running. This is why running slower, adding mileage slowly, and allowing rest and recovery days are so important when you’re making a comeback.

Don’t try to jump right into where you were before you took a break. You still have to start out slow.

2. Walk Before You Run

Before returning to running, you should be able to walk for at least 45 minutes (without pain if returning from an injury), says Paul. Walking reconditions soft tissue (muscles, tendons, ligaments, fascia, connective tissue), preparing them for the more rigorous demands of running, she says.

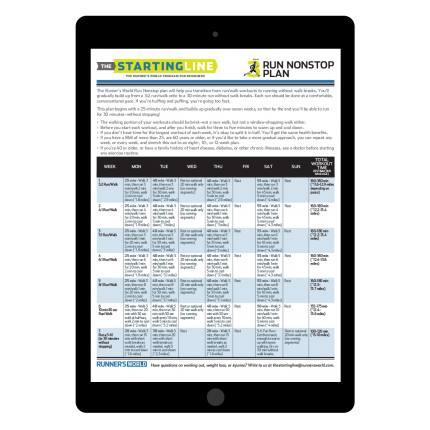

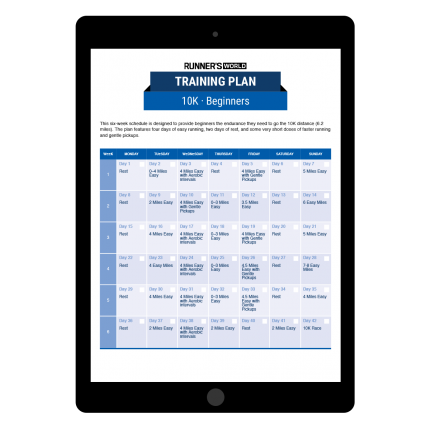

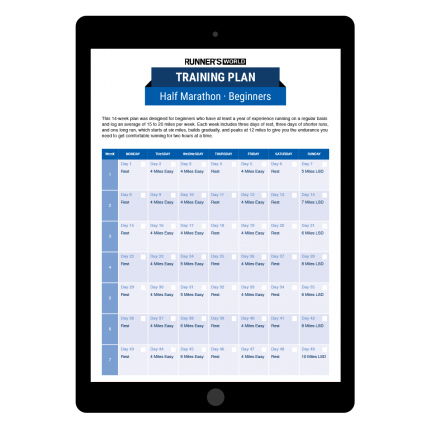

So, to make sure you’re getting your body prepared for running, first stick with short, easy runs, and take walk breaks. Start with three to four short runs per week so that you’re running every other day. Try five to 10 minutes of running at a time, or alternate between running and walking. If you need a place to start, try following a walk-to-run program that helps you slowly build up your running distance.

3. Practice Patience

Too many times a race or other goal encourages a runner to do more than they should too soon after injury, says Adam St. Pierre, an exercise physiologist and former running biomechanist. Even if you’ve been cycling, swimming, or doing other cross-training to maintain your aerobic fitness, remember that depending on the injury and the length of the layoff, it can take weeks or even months for your muscles, tendons, bones, and ligaments to get strong enough to handle running again. It takes the legs much longer than the lungs to adapt to new stresses, St. Pierre adds.

“Too often people get it in their head that they need to run for 30 minutes every day, or run and not walk, in order to make progress,” St. Pierre says. When starting after a long break, you need to check your ego at the door. Let your body adapt to the stress of a workout before you start adding more stresses!” Use the following guide:

- If you’re off 1 week or less: Pick up your plan where you left off

- If you’re off up to 10 days: Start running 70 percent of previous mileage

- If you’re off 15 to 30 days: Start running 60 percent of previous mileage

- If you’re off 30 days to 3 months: Start running 50 percent of previous mileage

- If you’re off 3 months: Start from scratch

Remember the 10 percent rule. If you’ve been off for three months or more, don’t increase your weekly mileage or pace by more than 10 percent, week over week. And you can always increase it less if you need to, say if you feel any aches or pains pop up or you’re just feeling generally wiped.

4. Get Strong

Strength training can help you tolerate a higher volume of running if done properly, says St. Pierre. But that’s only if you do it right, and if you specifically strength train your body to ready it for running again, says Colleen Brough, P.T., D.P.T., director and founder of the Columbia University RunLab.

“The key to having the hard work of a home exercise program payoff is carryover,” she says. “You might get strong in important target areas like the glutes and the lower abs, but you have to learn how to use this newfound strength during the run.”

Once you do exercises in a sitting or lying-down position, then add drills that mimic the components of running to help improve muscle coordination, timing, and biomechanics, so you don’t get injured and sidelined again.

3 Drills to Help Strengthen Your Stride

Do these drills as running “homework” during the first mile of your first runs. Repeat them again midway through the run and any time fatigue sets in or you hit the hills, Brough says. “We see running mechanics fall apart as we push the pace or distance,” she says. “These drills are an excellent way to correct that.”

1. Glute Push-Off Drill

As the foot hits the ground, squeeze your butt and drive the run forward by pushing off with the glute muscle. (Actually think about using that glute on the push-off.) Do this for 20 yards.

2. Midfoot Strike With Forward Lean

So many runners overstride, with their heels striking too far in front of their centers of mass. This increases force through the foot, ankle, and knee and has been linked to injuries, Brough says. To correct it, while you’re running, lean slightly forward while keeping your chest up, and think about landing less on your heel and more toward the ball of your foot or gently on a flat foot. You might pick an object about 20 yards away to aim for—say, a tree or a lamp post—and do the drill until you reach that target.

3. Cadence Drill

Increasing cadence or leg turnover seems to shorten the stride length and minimize the impact with which the foot hits the ground. Increase your cadence by switching to a quicker pace, or use a metronome app in place of music for about 20 yards.

5. Start Running Off the Road

Avoid just hitting the road again right away, says Paul. Instead, try heading to the track.

The track allows you to walk or run without getting too far from your car in the event that you need to stop. It’s a controlled, confined, flat, traffic-free area for a workout.

Starting on the treadmill can be a helpful place to start, too. The surface is forgiving, and you can control the pace and incline—and keep it steady throughout your run or run-walk—to suit your needs.

6. Don’t Overmedicate

Over-the-counter painkillers might make you feel better in the short term, but they can mask pain that tells you that you should stop. In fact, research shows that painkillers can sometimes do more harm than good, by causing gastric distress, and they may even detract from the benefits of a hard workout.

The ultimate rule: If you can’t run through pain, don’t run. Walk or rest instead.

7. Switch Up Your Cardio Activity

Working out every day will help speed up your cardiovascular fitness. But that doesn’t mean you need to run—and you probably shouldn’t jump right into running every day.

Instead, add two or three days of cross-training to your routine. Check in with your doctor to make sure that the particular mode of working out—cycling, rowing on a machine, swimming, or using an elliptical trainer—doesn’t worsen any injury, if that’s what kept you sidelined. But otherwise, just choose the activity you like best. Also, yoga, Pilates, weight training, and core exercises can help you get stronger.

That said, if you have done no exercise at all for three months, wait for two to three months before you cross-train; take rest days between your runs instead. That will ensure that your aerobic system gets enough recovery between workouts.