Runners often use the words “mobility” and “flexibility” interchangeably. You might, for example, see this hip-mobility video and think, “I should do that to help my flexibility.”

But mobility and flexibility have much different meanings. If you feel restrictions in your running stride, it’s important to know if those limitations stem from inadequate mobility or flexibility, because what you should do to improve the situation depends on the underlying problem.

To understand the difference between mobility and flexibility, think about making a pizza. You walk in the door after a good run and are hungry for dinner. A pizza sounds good! You reach into the refrigerator and pull out dough. The dough needs to be flattened into a crust. Should you stretch it or knead it? If you stretch it first, the dough is likely to tear and not pull far apart. This is because the dough is cold and has poor elasticity. In contrast, if you take a few minutes to knead the dough, it becomes much more pliable, so that when you form it into a pizza, it stretches easily.

In this analogy, stretching the dough relates to flexibility, and kneading the dough relates to mobility. Flexibility is the quality of bending easily without breaking. Flexibility is what you’re addressing when you do traditional stretching, with either short or long holds, with the goal of lengthening the tissue. A hurdler, for example, needs to be able to reach her leg in front of her torso to clear a hurdle. If her hamstring, the muscle in the back of the thigh, doesn’t allow her leg to stretch forward, she won’t be able to clear a hurdle with her lead leg. In her case, performing long-duration hamstring stretching may help to improve elongation of this tissue and help her clear the hurdle.

Mobility, on the other hand, is the ability to move, or be moved, freely and easily. It has less to do with stretching than with improving tissue pliability. This definition might sound remarkably similar to that for flexibility. The key differentiating word to me is “freely.” Think about a gymnast who shows up to training and says he feels tight. Most gymnasts have excellent flexibility. Does this “tight” gymnast really need to stretch more? After performing soft-tissue rolling or self-massage, he’ll likely feel warmed up, loose, and ready to go, even though he’s done nothing to target tissue length as he would with stretching.

Another key difference: Mobility can be defined as soft-tissue mobility, such as muscle, tendon, or myofascial, or joint mobility, which tends to be more the joint capsule, ligaments, and the joint itself. In contrast, flexibility pertains only to soft tissue.

Different strokes for different yokes

Because of these differences between flexibility and mobility, the best approach for improving them differs. Below we’ll look at tests for specific lower-body areas where you might feel restricted, and how best to improve what those tests reveal. First, though, here’s a little general information on addressing flexibility issues compared to mobility issues.

Improving flexibility can be done in a number of ways. One of the more common is static stretching. It entails moving just to a point of slight tension and holding the stretch for 30 seconds or more. If you’re looking for improvement in motion, you may find that a slightly less aggressive stretch that you hold for two to three minutes yields better results. Static stretching is best done after activity.

Join Runner's World+ for unlimited access to the best training tips for runners

Before running or other activity, dynamic flexibility work is a better choice. Dynamic stretching is movement similar to the activity you’re about to perform, such as leg swings before running. Rather than one long stretch, dynamic flexibility entails several movements of a few seconds each.

Treatment for soft-tissue mobility is often performed by using a foam roller, stick, or ball for self-massage. A typical duration is two to three minutes per area, but five to eight minutes might be called for in especially restricted areas. Tissue mobility is best performed before you run. Address the tissues that are restricted on each of your run days. As your mobility improves, you may find you don’t need this pre-run work as frequently, or even at all. Joint-mobility work is usually done with a band, strap, or your hands to provide more of an isolated joint stretch. You can also do mobility activities on non-running days.

Below are flexibility and mobility tests of key lower-body areas. Bear in mind that you might get less-than-great results from an area where you seldom experience injury. Similarly, you might perform well in a body area that’s a frequent site of injury. Restrictions in one area can often lead to injury elsewhere. That’s why it’s important to do all of these tests and, if warranted, to follow through with the prescribed treatment.

Foot and ankle assessment and treatment

Some of the most common running pathologies involve the foot and ankle, such as plantar fascia or Achilles tendon issues. Do these two self-assessments to determine if you might have a limitation that’s contributing to injury or poor mechanics.

→ Want more tips like this? Join Runner’s World+ today for exclusive access to expert strategies!

Runner’s Wall Stretch – Calf Flexibility

Place your hands on a wall in front of you with your back foot about two feet behind the front. Are you able to keep your back foot straight and heel on the ground? If so, you likely have appropriate calf flexibility and ankle mobility.

If you feel tightness in your calf but are able to keep your heel on the ground, you most likely have just a soft-tissue restriction, and a mobility treatment is recommended. If you aren’t able to keep your heel on the ground, perform the half kneeling assessment below to check if ankle mobility is limiting your movement.

Calf Mobility Treatment: Use a foam roller or massage stick to massage your calf, all sides, as needed if tight.

Half Kneeling Assessment – Toe, Foot, and Ankle Mobility

Kneel on one knee with the other leg in front and foot flat on the floor. Tuck your back toes under. Now, with your leg in front, shift your knee forward and see how far in front of your toes your knee is able to move without your heel lifting. Make sure your knee and foot point straight ahead. You can do a simple measure of this distance by placing a ruler on the ground and using a pole of sort, as shown in the video.

First, assess that your toes on the back foot can bend freely. If your toes are more vertical to the ground compared to parallel, you may need to work on movement of the big toe.

Toe Mobility and Flexibility Treatment: Roll the bottom of the foot with a lacrosse ball to improve plantar fascia mobility, or sit on your heels, with knees on the ground and toes tucked under, for toe flexibility.

Second, shift your front leg forward to assess how far in front of your toes your knee is able to go. If this measurement is less than three inches, you may have ankle restriction and should consider working on your ankle mobility. If this number is easily three inches or more, but you weren’t able to perform the Runner’s Wall Stretch, consider the calf flexibility option.

Ankle Mobility Treatment: Improve ankle mobility by placing a band around a firm object and then around the back of your ankle, pulling in forward. Perform the same motion as the assessment working to move your knee in front of the toes.

Calf Flexibility Treatment: The Runner’s Wall Stretch can be used as your treatment. Shorten the distance your rear foot is behind you. Find a comfortable distance where your foot is straight and your heel is down to allow a light calf stretch.

Knee assessment and treatment

Runner’s knee is a common running injury that involves irritation around the patella in the front of the knee. One of its causes is excessive compression of the patella against the femur from poor knee movement. This could stem from resistance when bending or straightening. Here are a few easy tests you can perform to make sure your knee is moving freely.

Seated Heel Slide Assessment – Knee Bending Mobility

Sit with your legs in front. Pull back on your foot using a strap. Your knee should be able to bend to a distance that allows your foot to be close to your glutes. If not, you should add knee mobility to your routine.

Knee Bending Mobility Treatment: Using a foam roller or massage stick, spend roll through the front of your thigh. Make sure to get the outer, front, and inside portions.

Stomach Strap Stretch Assessment – Knee Flexibility

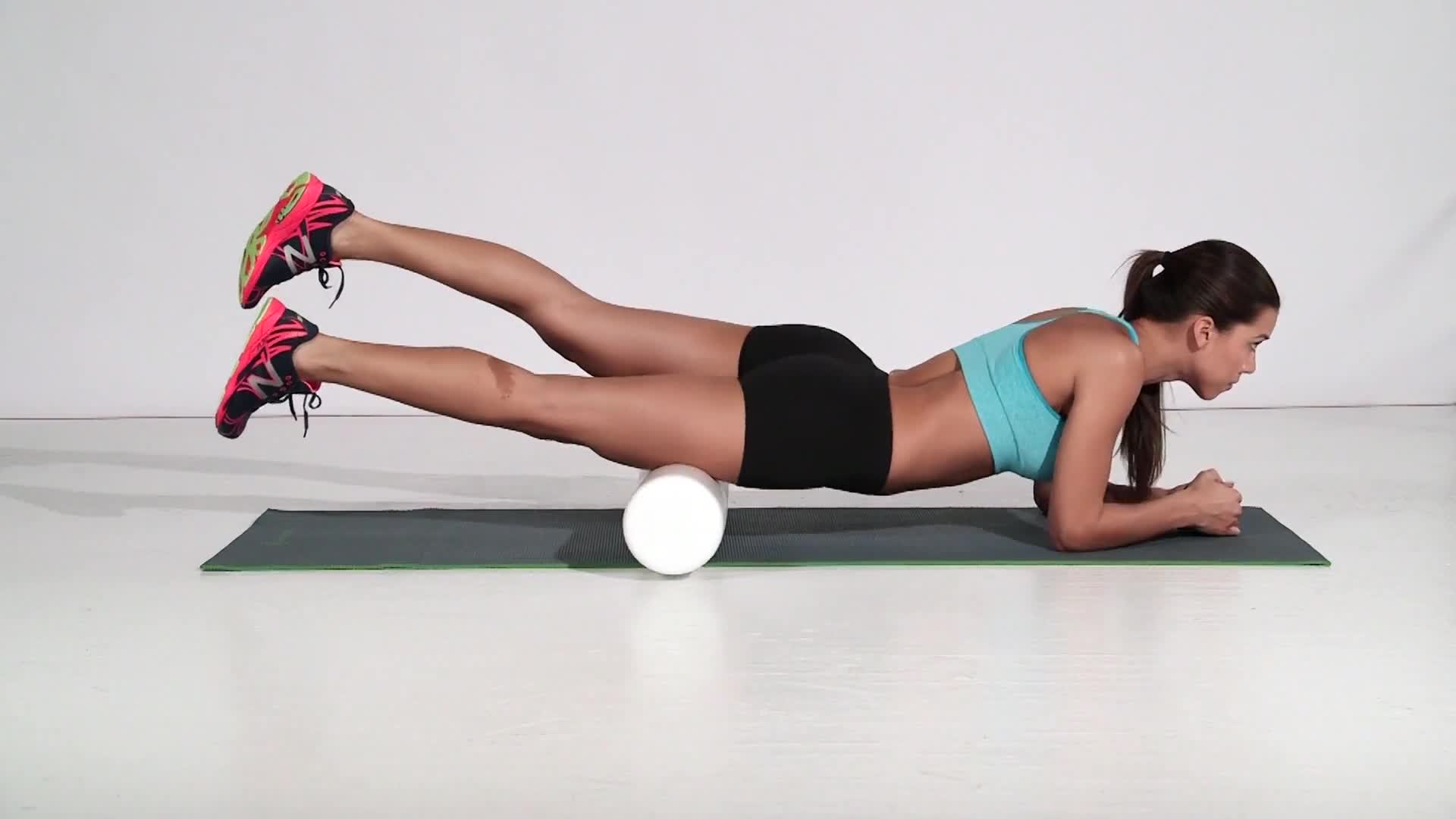

Lie on your stomach with a strap around your ankle. Pull your back foot toward your glutes. Your heel should come within about six inches of touching. If not, do the above mobility work and also include flexibility to your program.

Knee Bending Flexibility Treatment: Performing the same position as the strap assessment is a great way to isolate your thigh. Keep your hips flat on the ground and hold the stretch position with your ankle towards you.

Seated/Supine Strap Straightening – Knee Straightening Mobility

Lie with your legs in front of you. Your knees should be straight with minimal space underneath them. If not, you may have a mobility issue of the knee. If your knees do line up straight with minimal space underneath, sit up and place a strap close to your toes. Now pull back on the strap while pressing your knee down. Does your knee flatten to the ground and heel elevate slightly? If you find restriction in making this happen or an imbalance in right to left, you may have a flexibility issue. Try the knee-straightening stretch below in conjunction with the above calf stretch to address.

Knee Straightening Mobility Treatment: Using a foam roller or massage stick, roll through your calf and back of the thigh.

Knee Straightening Flexibility Treatment: Use the same strap technique as the assessment (see above), but perform while on your back. Pull your foot up while keeping your knee straight until you feel a light stretch behind your knee.

Hip assessment and treatment

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint, and therefore it has more planes of movement than the foot, ankle, and knee. This makes it more challenging to assess with one isolated test. However, one of the limitations that’s most often seen in runners is lack of hip extension, or the ability for the thigh to move behind you easily in your stride. This can lead to excessive load on the hips and back, and constrain your overall stride length. Try this simple test to assess your hip extension.

Bed Leg Hang – Hip Extension Flexibility

Lie on your bed with your hips at the edge. Grab one knee, pull it up to your stomach, and hold. Assess the other leg to see how low or high it hangs. If the thigh is level with the bed, or sloping downward, your hip flexibility is appropriate. If it’s sloping upward or your leg is deviating outward, you could benefit from hip flexibility. If your flexibility is appropriate but you still notice the feeling of restriction in your hip, try performing hip joint mobilization or soft-tissue mobility to the iliopsoas, or hip flexor.

Hip Extension Flexibility Treatment: Kneel on the side you wish to stretch and place the other leg in front. This position is the same as the Half Kneeling Assessment above. Now, tuck your pelvis so that your hips are level front to back. Squeeze your glutes to engage them on the leg you’re stretching. Lightly shift your hips forward until you feel a stretch in the front of the hip and top of the thigh.

Hip Joint Mobility: Place the involved leg inside a long and firm resistance band. Pull the band up as high up on the leg as possible. Now, step away from the band so that it’s pulling your hip laterally. Place this leg behind you so that you’re in a lunge position. Perform three sets of 10 lunges while the band pulls laterally on the hip.

Hip Soft-Tissue Mobility: Use a ball to roll through the front of the hip. Focus on keeping the ball more lateral, just to the inside of the front of the pelvis. You can also roll just below and to the outside of this to include rolling of the tensor fascia lata which is often limited in conjunction with the iliopsoas.

Back to the bigger picture

As you go through these assessments, you may find that there are differences between your left and right sides. Symmetry in movement is important for runners. If you notice that one side of the body has a limitation and the other doesn’t, focus your initial treatment on the involved side only. After two weeks, reassess and see if your symmetry has improved. You may find that correcting an imbalance takes months or may require additional treatment.

It’s important to recognize that there isn’t one sole treatment that’s best for everyone. If you try these exercises and find that your range of movement isn’t improving, consider performing the exercises for longer durations and doing them more than once a day. If you continue to have a pathology, see a medical professional. Alternative treatment, including strength training, stabilization work, or biomechanics re-education, may be necessary.

Now watch this:

Daniel Frey, D.P.T., is the co-owner of Finish Strong, a sports-centric physical therapy clinic in Portland, Maine. A lifelong runner, Daniel is the author of The Runner’s Guide to a Healthy Core.