Next time you or your child’s knee hurts, check for a little bump just below the patellar tendon. If you feel something, it might be Osgood-Schlatter’s disease. Though the name sounds ominous, it isn’t as scary as it sounds. About 10 percent of adolescents—whose bodies are growing and changing as they exercise—experience it.

So if your child is suffering from Osgood-Schlatter’s, don’t fret—it’ll go away on its own. But if you are experiencing adult complications as a result of Osgood-Schlatter’s, things might be a little more complicated. Runner’s World talked to Cathy Fieseler, M.D., chairperson of the Road Runners Club of America Sports Medicine Committee and member of the board of directors of the American Medical Athletic Association, to share everything you need to know about the disease, including causes, treatment, and more.

What causes Osgood-Schlatter disease?

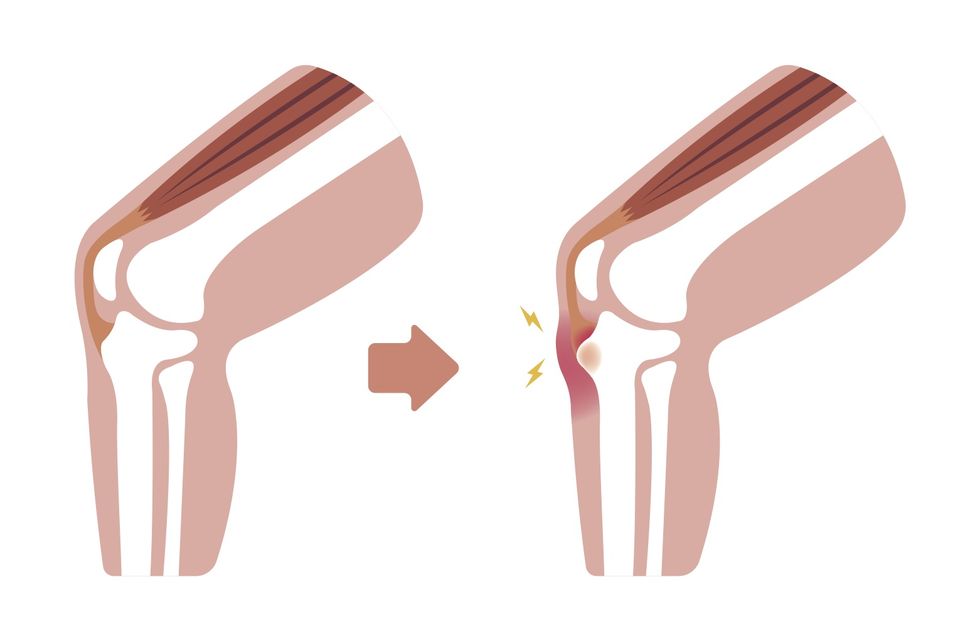

Osgood-Schlatter disease is not actually a disease, rather a condition in which the tibial apophysis is inflamed due to traction by the patellar tendon, Fieseler says.

More From Runner's World

Translation: During childhood when your body’s still maturing, there are growth plates that separate the shaft of the tibia (a.k.a. the shinbone), known as the diaphysis, and the end of the shinbone, known as the epiphysis. This allows the bone to lengthen over the course of childhood and adolescence. The diaphysis and epiphysis eventually fuse together when you’re finished growing.

There is also a developmental outgrowth that hangs over the front of the shin, just below the knee. This is called the apophysis, and it attaches the patellar tendon to the shinbone at a point called the tibial tuberosity. Eventually, this bone piece will fuse with the shin just like the diaphysis and epiphysis.

The patella, or kneecap, sits right within the tendon that connects the quadriceps to the shinbone. Contraction of the quadriceps straightens the knee. By repetitively contracting the quadriceps, whether through running, jumping, or even kicking, the apophysis becomes inflamed, causing the adolescent to suffer from Osgood-Schlatter disease.

When does this typically occur? “Girls are typically going to have a problem between ages 10 and 13,” Fieseler says. “In boys, it’s a little bit later, like 11 or 12 up to 15.”

Join Runner's World+ for unlimited access to the best training tips for runners

How do you treat Osgood-Schlatter disease?

The main symptom is pain and swelling just below the knee, which can range from mild to severe depending on the case. There will be a small area of swelling at the tender site. Activities that contract the quads repetitively—like running or jumping—cause more severe pain, as do direct blows to the area.

Treatment usually involves rest and pain management, says Fieseler. She recommends ice, activity modification, and sometimes extra padding. Some kids she’s worked with use patellar straps, which take some tension off the tibia.

Can adults get Osgood-Schlatter disease?

It’s pretty uncommon for adults to come down with Osgood-Schlatter’s, says Fieseler. Irritation stops once you’re fully grown, because the cartilage in the growth plates turns to bone, and bone is much less prone to inflammation than cartilage.

However, there can be lasting effects from childhood Osgood-Schlatter’s. You might be left with a painless bump below the knee where the pain used to be. In very rare cases, if you overwork the tibial tuberosity when experiencing Osgood-Schlatter’s as a kid, little pieces of bone could fracture off. When bending the knee, the patellar tendon can pinch these pieces—called ossicles—against the front of the knee, causing severe pain. Doctors would then surgically remove the ossicles to fix it.

Again, that outcome is only in rare cases. Ninety percent of cases resolve either on their own or with some treatment.

Chris Hatler is a writer and editor based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, but before joining Runner’s World and Bicycling, he was a pro runner for Diadora, qualifying for multiple U.S. Championships in the 1500 meters. At his alma mater the University of Pennsylvania, Chris was a multiple-time Ivy League conference champion and sub-4 minute miler.