There’s a good chance that locker room talk for female runners includes mention of urinary leaking. Incontinence can affect women of all ages, but it’s more common in older women. In fact, more than 40 percent of women over the age of 65 experience leaking, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Leaking is a symptom of pelvic floor dysfunction, explains Lauren Garges, P.T., W.C.S., director of the women’s health program at St. Luke’s University Health Network in Pennsylvania.

“Pelvic floor dysfunction is an umbrella term that covers a number of diagnoses,” Garges, a runner, tells Runner’s World. “It means the muscles that form a sling of support at the base of the pelvic bone are not working optimally.”

More From Runner's World

The muscles in the pelvic floor are known as your deep core muscles, and they stretch from the pubic bone to the tailbone and from side to side. When they’re not working correctly, they could be too weak—picture a loose hammock—or they could be too tense—picture a hammock pulled taught.

In both cases, Garges says, urinary leaking is a common symptom, and she makes an important point: “Leaking is common but not normal.”

“Women should have full pelvic control—that means no leaking—for their entire life,” she says. “You should never leak. It’s not normal. If you’re leaking it’s an indicator that something is likely happening with the pelvic floor.”

As a women’s healthcare professional, what bothers Garges the most is how normalized leaking has become, even if it’s talked about in hushed tones.

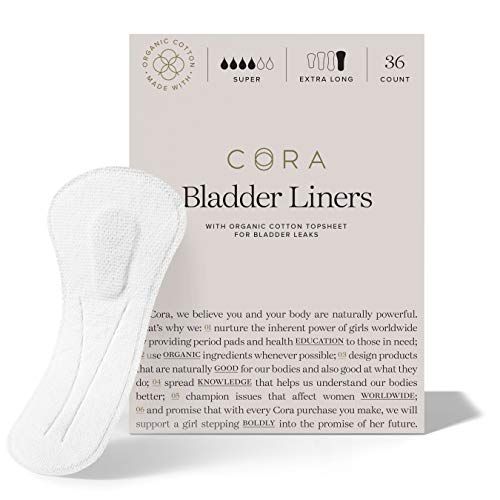

“In society we laugh it off,” she says. “Women put on a Poise pad and suffer through it forever. That’s frustrating to me because it has become normalized, and that’s not how it should be.”

What Does Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Feel Like?

You may be experiencing pelvic floor dysfunction and not even realize it because you don’t know what to look for.

The best way to get a sense of the strength (or lack thereof) of your pelvic floor is to engage your muscles by doing the infamous Kegel exercise: Take a deep breath and when you exhale slowly contract the muscles you would use if you’re trying to stop the flow of urine. When contracting, imagine your muscles are an elevator that’s slowly rising. And then relax your muscles completely.

If your muscles are weak, you should still be able to relax them, even if it’s just a little bit. Women might also experience organ prolapse: when a pelvic organ—uterus, bladder, or rectum—drops into or out of the vagina.

If your muscles are too tight, however, you may not be able to do a kegel at all or be unable to release completely because the muscles are already contracted.

“Muscle tightness is harder to self-diagnose,” Garges says.

With tightness, you might also experience pain with sexual intercourse, inserting a tampon, or during gynecologic exams. Runners might have pain while running.

While men don’t experience pelvic floor dysfunction (yes, men have pelvic floors) nearly as frequently as women, they might suffer from pain while sitting, urination, sexual intercourse, and difficulty in trying to pee. Those are indicators of muscle tightness, Garges says.

What Are the Causes of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction?

In women, there are three causes of pelvic floor dysfunction, Garges explains: muscle weakness or tightness, pregnancy and childbirth, and the hormonal effect of menopause.

During pregnancy, women experience a postural shift—their centers of gravity move forward and put increased strain on the bladder.

“As the uterus rises above and sits atop the bladder, you have added weight on [the pelvic floor],” Garges says.

Once women hit menopause, they have lower levels of estrogen, which decreases their muscle tone—pelvic and otherwise—Garges explains. That contributes to loss of bladder control.

Running—while pregnant or not—adds another stress because of gravity and ground reaction force. Ground reaction force, Garges explains, is the force your body absorbs every time your foot hits the ground.

“You have gravity going down and ground reaction force coming up, and they meet at the midpoint in the pelvic area,” she says. “Your pelvic floor muscles are absorbing a ton of impact, and when you have all of these forces hitting at once, if your pelvic floor has a deficit, that’s when leakage occurs.”

Leaking after giving birth, Garges says, is a sign that you might be pushing your body too hard. While she encourages women to run during and after pregnancy as they feel comfortable, it’s important to listen to your body.

That might mean slowing the pace or duration, or changing the surface on which you’re running.

“Change something so that when you run you do not leak. If you leak at mile three, finish your run at mile 2.5 while you’re healing and strengthening,” she says.

Garges also points out that most OB-GYN physicians don’t have a background in pelvic floor care, and even if they say you can return to normal activities after childbirth, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re ready.

In 2019, a team of physiotherapists updated the guidelines for women seeking to return to running after childbirth. They doubled the recovery time from six to 12 weeks.

“There’s validity to waiting,” Garges says. “In the long term, your pelvic floor will be a lot better off.”

New York-based pelvic floor physical therapist Abby Bales, P.T., D.P.T., C.S.C.S., owner of Reform PT, goes on to point out that because the pelvic floor muscles are made up of the same fibers as your biceps or hamstrings, for example, the same lifestyle stressors can contribute to dysfunction. That might mean dehydration, lack of sleep, and emotional or physical stress, which, Bales says, certainly affect new moms.

“Mom might not be drinking [enough water] because she’s afraid of leaking, and dehydration isn’t helping her muscles,” Bales says.

How Can You Prevent and Treat Pelvic Floor Dysfunction?

Don’t despair (and definitely don’t stop running!)—there’s good news: Pelvic floor dysfunction is both easily treatable and preventable.

To fix pelvic floor dysfunction, pelvic floor therapy will focus on strengthening your deep core and pelvic floor muscles, Garges says. Often a runner will only have to see a physical therapist once to receive an official diagnosis and exercises designed to treat tightness, weakness, or lack of tone. The magic bullet, so to speak, of pelvic floor exercises is the Kegel.

There are two ways to properly do a Kegel exercise: One builds endurance and the other is for quick muscle reflexes. Garges likes to put it in terms runners can understand: “The long Kegel is for your slow-twitch muscles, and the quick Kegel is for your fast-twitch muscles.”

A long Kegel means you will exhale from five to 10 seconds while contracting your pelvic floor muscles. Garges recommends 10 repeats, two to three times a day. These Kegels will improve your pelvic floor strength for activities like running and childbearing.

The short Kegel strengthens muscles that prevent leaking during short, powerful bursts like laughing, sneezing, and coughing. Garges explains you can breathe normally and contract your muscles for just one to two seconds.

When it comes to prevention, it’s all about being aware of pelvic floor dysfunction.

“If you have a healthy pelvic floor, you’re not going to have a problem and you don’t have to do anything,” Garges says. “You won’t leak, and the floor is going to do its job.”

When things start to change, she says, that’s when you want to nip it in the bud to prevent longer-term problems.

“If someone has a baseline of being fine with no symptoms, I’m not going to tell them to do exercises to change it,” Garges says.

Heather is the former food and nutrition editor for Runner’s World, the author of The Runner’s World Vegetarian Cookbook, and a seven-time marathoner with a best of 3:31—but she is most proud of her 1:32 half, 19:44 5K, and 5:33 mile. Her work has been published in The Boston Globe, Popular Mechanics, The Wall Street Journal Buy Side, Cooking Light, CNN, Glamour, The Associated Press, and Livestrong.com.