We’re data junkies, so we’re always studying the numbers after runs, dissecting our training logs like an astrologist decoding a birth chart. Yet time and again, we’ve learned most factors related to running—pronation, stride, type of running shoe, “racing weight”—are dependent on the individual. That includes cadence, too.

The golden standard for cadence used to be 180 strides per minute (SPM), after legendary coach Jack Daniels tallied pro runners’ steps at the 1984 Olympics. All that counting was in vain—sorry, coach—since that “magic number” has since been debunked.

A study analyzed the cadence of ultrarunners competing in 2016’s 100K World Championship road race. Sure, the overall average was 182 SPM, quite close to Daniels’s 180. However, when researchers looked closer at step frequency, it varied from 155.4 to 203.1 SPM. They also found race fluctuations weren’t influenced by age, weight, sex, experience, or fatigue. The two factors that did correlate with a higher cadence were speed and height. The shorter the runner, the more steps that runner took compared to taller competitors.

More From Runner's World

Still, what can cadence teach us and how can we apply it to training?

One takeaway is to review your cadence over past workouts (most GPS running watches measure it automatically), and mentally check if you’re overstriding—which can cause injury—when you up the tempo during runs.

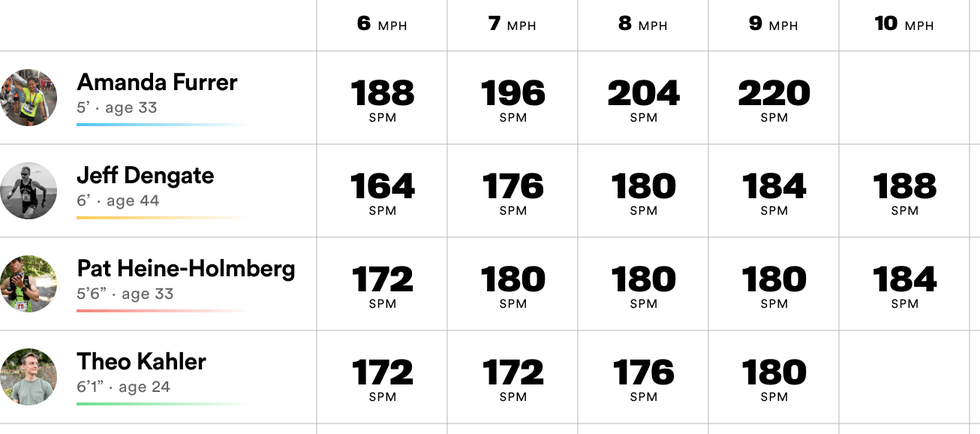

Curious to see how my coworkers and I stacked up, I had each of us run on a treadmill for approximately 10 minutes to observe step frequency and whether there’s any variance at different speeds. At a zero percent incline, we each ran 6, 7, 8, and 9 mph (two nudged it up to 10). Similar to the study, I wanted to see how height, speed, age, gender, form, and fitness (some of us were in the midst of marathon training) influenced cadence.

After spending an afternoon playing back the video and painstakingly counting everyone’s steps at each interval (and comparing smartwatch data, if they wore one), I made a table of everybody’s step frequency at different speeds. Our test showed that increasing speed did indeed increase step frequency. It also showed that shorter runners take more steps per minute compared to taller runners. At 9 mph, my cadence was dramatically higher than membership editor Theo Kahler’s— a whopping 40 SPM difference, which is not surprising considering he’s a foot taller than me.

One thing to consider is that even though treadmill running is ideal for collecting data in a controlled, indoors setting, your form is hindered by the mill’s parameters and push-off is slightly assisted by the moving belt. I had some of our testers send me their past race data on Strava for comparison.

It turns out treadmill pace and SPM aligned with their road race pace and cadence. For example, at a recent marathon, where I ran at 7:00 per mile, my average cadence was 207 SPM. At the same pace, video producer Pat Heine-Holmberg maintained 181 SPM at 2019’s Runner’s World Half Marathon. Runner-in-Chief Jeff Dengate averaged 187 SPM at 6:30-pace during the 2019 Chicago Marathon.

Cadence is relative. As I observed during my video counting, there’s not one SPM that fits all. One way to use this data is to study your own cadence at past races and see how your speed factors in and how you felt after your run. Overstriding may be the postrace injury culprit.

For me, personally, I’m satisfied knowing I take more steps than my taller colleagues. I run their pace by taking more steps and still feel just as fresh. So, yep, this test proves I’m superhuman.

Amanda is a test editor at Runner’s World who has run the Boston Marathon every year since 2013; she's a former professional baker with a master’s in gastronomy and she carb-loads on snickerdoodles.