We always did the 12-minute run on the third day of cross country practice, a sure sign the fun of summer had ended. My high school coach, Greg Wilson, would bring dozens of students to a local track in our Kansas City suburb at 6 a.m., click his stopwatch and force us to run around the oval, lap after lap, as many as we could finish. The local police had their training center atop a hill nearby, and, below it, our track felt like a jail, runners trapped, splayed across the lanes, many walking after a few minutes. When Wilson shouted into a megaphone to stop, even the well-conditioned few were hunched over and heaving. Whether you were one of the fastest or slowest runners, the 12-minute run’s induced misery did not discriminate.

I assumed for years my coach had concocted this excruciating workout. In fact, my pain was universal.

The 12-minute run was and is perhaps the world’s most effective and popular conditioning test. I was enduring the same torture as Pele did as a soccer star, as Michael Jordan did as a college basketball player. And all of the pain stemmed from an invention by Dr. Kenneth Cooper.

More From Runner's World

Cooper has achieved international fame for inspiring the modern exercise movement through his book Aerobics. He’s less known for creating the 12-minute run, or, as others call it, the Cooper Test. This month marks the 50th anniversary of the Cooper Test’s publication, and in that time the 12-minute run has been used by championship World Cup, NFL, and college basketball teams, FIFA referees, police recruits, and thousands upon thousands of high school and amateur athletes worldwide, many of whom, like high school me, have no idea how the test came to be and what makes it an ideal conditioning tool.

“I would never have predicted it,” Cooper says, reflecting on the surprising longevity of his test.

When he speaks, Cooper sounds like a mix between drill sergeant and historian, reeling off dates and results from decades-old studies and rarely stopping for air.

He is 86 and still works full time at Cooper Clinic in Dallas, seeing patients as famous as George W. Bush and collecting data on the fitness levels of more than 100,000 people. China recently hired him to whip its 300 million obese citizens into shape.

People talk to him about the torture of the 12-minute run all the time, all over. At a recent fundraising event he cohosted with Laura Bush, author John Grisham approached and told him, “I hate you. We had to take that darn 12-minute test so many times.”

The premise of the Cooper Test is simple: Finish as many laps as possible in 12 minutes. The number completed acts as an indicator of one’s VO2 max, or the maximum amount of oxygen one can use during vigorous exercise. (It can also be reversed, with athletes running for 1.5 or two miles and the time indicating VO2 max.) A VO2 max between about 34 and 42 is considered fair and 43 and 51 good. Anything over 51 is excellent.

For adult men in their 20s and 30s, between five laps is a “fair” 33.8, six is a “good” 42.6 and seven is an “excellent” 51.6. Eight correlates with a VO2 max of 60. For women, basically subtract one lap from each range—four laps is fair, five is good and six is excellent. By middle age, five laps for a woman or six laps for a man would be considered excellent.

At my St. Thomas Aquinas High School, the varsity male runners would get eight to nine laps. The top female runners would get somewhere between seven and eight.

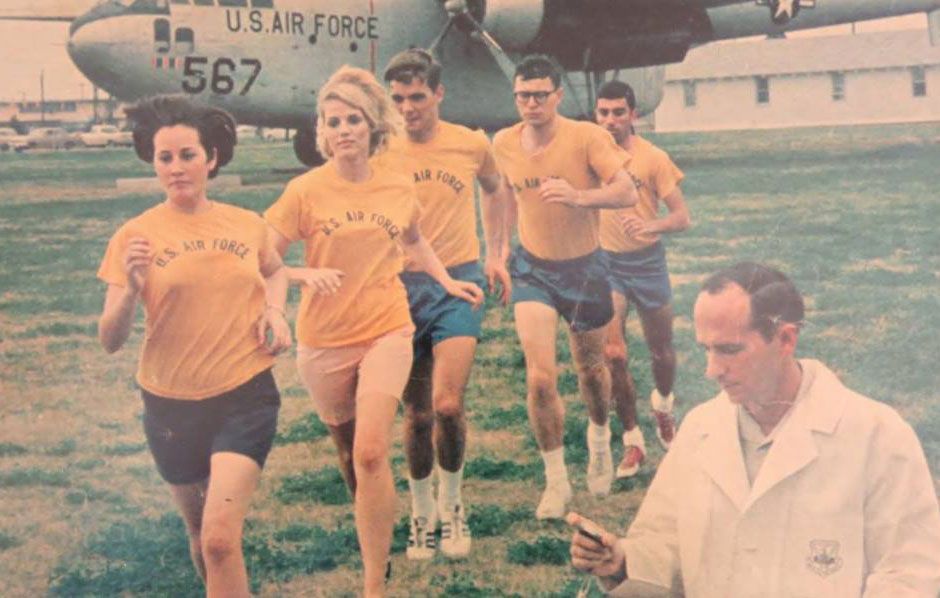

Cooper invented his famous test while working for the Air Force. Political and military leaders knew Americans were trailing our European peers in fitness. Cooper had seen it on an excursion to Austria. As for the Soviets, neither Cooper nor anyone knew whether they were truly in superior physical condition, but, Cooper says, “I had a strong feeling.”

At the time, a person’s VO2 max, the maximum amount of oxygen one can use during vigorous exercise, could be determined through a treadmill test involving a respiratory valve and gasometer. It would take forever to conduct these for thousands of Air Force members.

Cooper’s 12-minute run improved on other efforts for gauging fitness, such as the 600-meter run and the 3-mile run, with his test determining VO2 max with 90 percent accuracy. And most of the men’s VO2 max levels left much to be desired.

“It was pathetic in the first test,” he says. “They weren’t getting close to one and a half miles.”

The results were published in the January 1968 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, the article stating, “Because of the high correlation with maximal oxygen consumption, it can be assumed that the 12-minute field performance test is an objective measure of physical fitness reflecting the cardiovascular status of an individual.”

And with that, Cooper had given the world an accurate, simple way to determine a person’s fitness level, one that has been validated over and over.

The 12-minute run may have remained with the armed forces, which still use a version of it today, if not for the success of Aerobics and a Brazilian soccer coach named Claudio Coutinho. Cooper’s book intrigued Coutinho enough bring the doctor on as a consultant. Cooper tailored a workout regimen that included the 12-minute run as a way to gauge the soccer players’ fitness levels. At first, the national team’s average distance was seven laps, or 2,800 meters. After a year of Cooper workouts, they had progressed to averaging 8.25 laps, or 3,300 meters. They won the 1970 World Cup, closing out many of their games with second-half comebacks, drawing praise for their superior conditioning.

“The true story is we got them in great shape,” Cooper says, “but they had Pelé playing for them.”

The success of Brazil, Cooper believes, led other teams to embrace the Cooper Test, and it went viral. Don Shula made his Miami Dolphins players complete a 12-minute run every preseason. Dean Smith held a 12-minute run for his basketball players on the first day of school, and North Carolina has continued the tradition to this day. For the Super Bowl-winning Dallas Cowboys in the 1990s, coach Jimmy Johnson favored the 12-minute run over other popular conditioning tests, such as making players run 16 100-yard sprints, because he knew you couldn’t fake your way through it.

“Even if they were a great athlete,” Johnson says, “if they weren’t prepared they wouldn’t be able to pass.”

Rarely is there an explanation for the test’s origins. It’s simply passed on like a good recipe, coach to coach, athlete to athlete. Johnson, for instance, can’t remember why he began using the Cooper Test, and, despite coaching a few miles from Cooper’s fitness institute in Dallas, had never heard of Cooper until recently, let alone knew Cooper invented the 12-minute run.

These days at the college and professional levels, the 12-minute run has slid in popularity. Rather than endurance runs, coaches are opting for sprint work for conditioning tests, believing shorter distances better replicate in-game experiences and reduce wear and tear. Soccer has kept the test alive, from college teams to FIFA referees to players in the top European leagues. Last fall, a friend of Cooper’s was visiting with the lead trainer of S.S. Lazio, a renowned Italian soccer club. He asked the trainer what the team used for judging fitness. His response? The Cooper Test.

Matt Doherty, a North Carolina player in the early 1980s, kept using the Cooper Test as a coach, at North Carolina from 2000 to 2003 and a few years later at Southern Methodist University in Dallas (where he got to meet Cooper).

“I still think there’s a place for long distance running,” says Doherty, now the associate commissioner of the Atlantic 10 athletic conference. “Maybe that’s because I liked it. But I think the mental side of it is the challenge. I like to challenge the athlete mentally with the distance running.”

At North Carolina, Doherty wanted to get eight laps every year, and in the summer he and fellow players like Jordan would routinely run 4.5 miles after scrimmaging with Carolina alumni to get in shape for the 12-minute run.

Their dedication is indicative of the 12-minute run’s magic. The test does more than yield an athlete’s VO2 max. It engenders a sense of dread and accomplishment. Nobody wants to be out of shape for something as difficult as the Cooper Test, so you run more. And when you feel good about taming the Cooper Test, you want to run more, too, sometimes long past your athletic prime.

Hall of Fame quarterbacks Roger Staubach and Troy Aikman, both forced to do Cooper Tests in their playing careers, still regularly run at the Cooper Clinic, competing against each other’s benchmarks on treadmill tests. And after telling Cooper how much he hated the 12-minute run, Grisham added, “I’m still running.”

Fifty years later, Cooper vouches for the test’s importance through his continuing studies. One’s fitness level, most easily gleaned through the results of a 12-minute run, can be predictive of a longer, healthier life. His institute’s pilot studies have shown middle-aged men and women in the top quintile of Cooper Test results, about six laps for men and five for women, will see lower healthcare costs and reduced chances of heart disease and other chronic diseases later in life.

Cooper said his son is working on an app that would allow runners to take a 12-minute test anywhere and see their results compared against standards for their age group. (This calculator provides VO2 max and a rating.) For now, the best way is still on the track.

I tried a Cooper Test recently with my friend Hunter. At my high school peak more than 10 years ago I could get close to 8.75 laps. As I labored around Temple University’s track in Philadelphia, struggling to reach eight, I sensed why the workout has earned near-universal renown for its difficulty. It’s the realization the watch on your wrist is an enemy. No matter how fast you run, it won’t end sooner. You can’t escape. The 12-minute run always means 12 painful minutes.