It was a typically modest response from Jesse Owens as, days before the 1936 Summer Olympics, he entertained a young reporter who inquired how he’d react at the sound of the first starter pistol. Going fast was hardly in doubt: it was all the sensational track and field athlete had done since his youth, leaving onlookers bewildered whenever he graced a track meet. His astonishing speed had earned him enough accolades to guarantee a spot—in fact, three—at the 11th Olympiad in Berlin.

He was the only U.S. team member who qualified for multiple events: the 100 meters, 200 meters and long jump (then known as the broad jump). He’d be among other notable Black teammates, including revered sprinters Ralph Metcalfe and Frank Wykoff , but “the one-man track team from Ohio State” affirmed what everyone expected of the prodigious 22-year old. He would be the highlight of the Games, and the world would be eagerly watching. But as a Black man headed to Nazi Germany, his fabled appearance would come at one of the most appalling periods in history, and it would be more momentous than the spectacle itself.

Like his displays at meets across the U.S., Owens’s first Olympic outing, on August 2, 1936 was a stunner. He effortlessly won his first 100 heat by more than six meters, equalling his own world record of 10.3 seconds. Later, in the afternoon’s quarter finals, he’d knock this down to 10.2 seconds—though officials disallowed it as a new record because of the tailwind. The next day, his semifinal heat drew him against Wykoff, who’d won gold in the 4 x 100 relays in 1928 and 1932. He overtook the Iowan at 80 meters to beat him by a tenth of a second in 10.4. Gold in the final, as ever the prestigious centerpiece of the Games, was not guaranteed, though. To claim it, Owens needed to ensure his unpredictable starts – his only flaw – didn’t allow the formidable Metcalfe, his closest rival and 1932 Olympic silver medallist in the 100m, to take the prize.

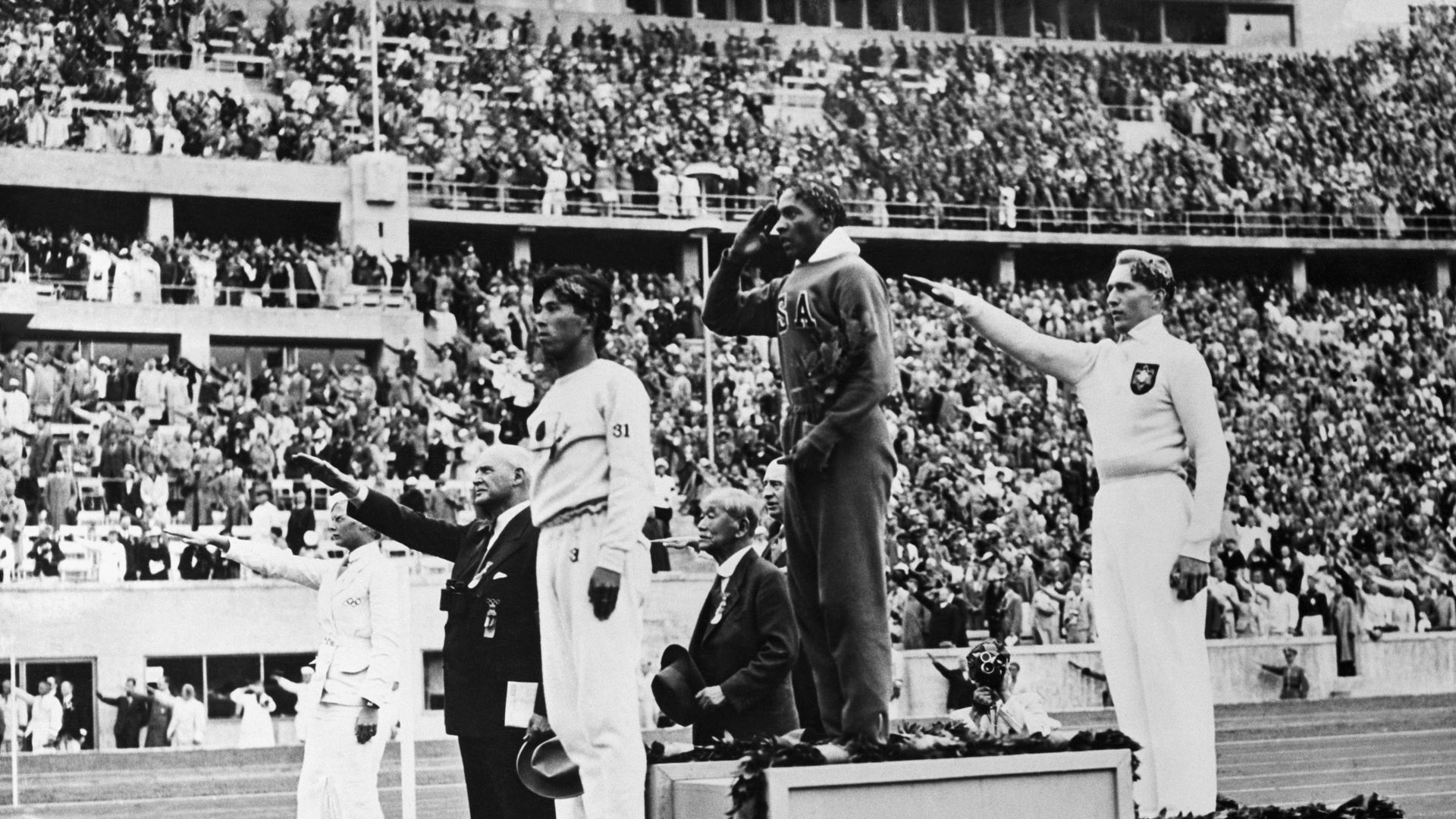

To add to the tension, Owens was positioned in the inside lane, which was particularly muddy in the poor weather. However, a perfect start propelled him down the track and though Metcalfe closed the gap in the last 20 meters it was too late: Owens won gold in 10.3 seconds, equaling his world record. “This is the happiest day in my life,” he said afterward. “I guess it’s the happiest I will ever have.”

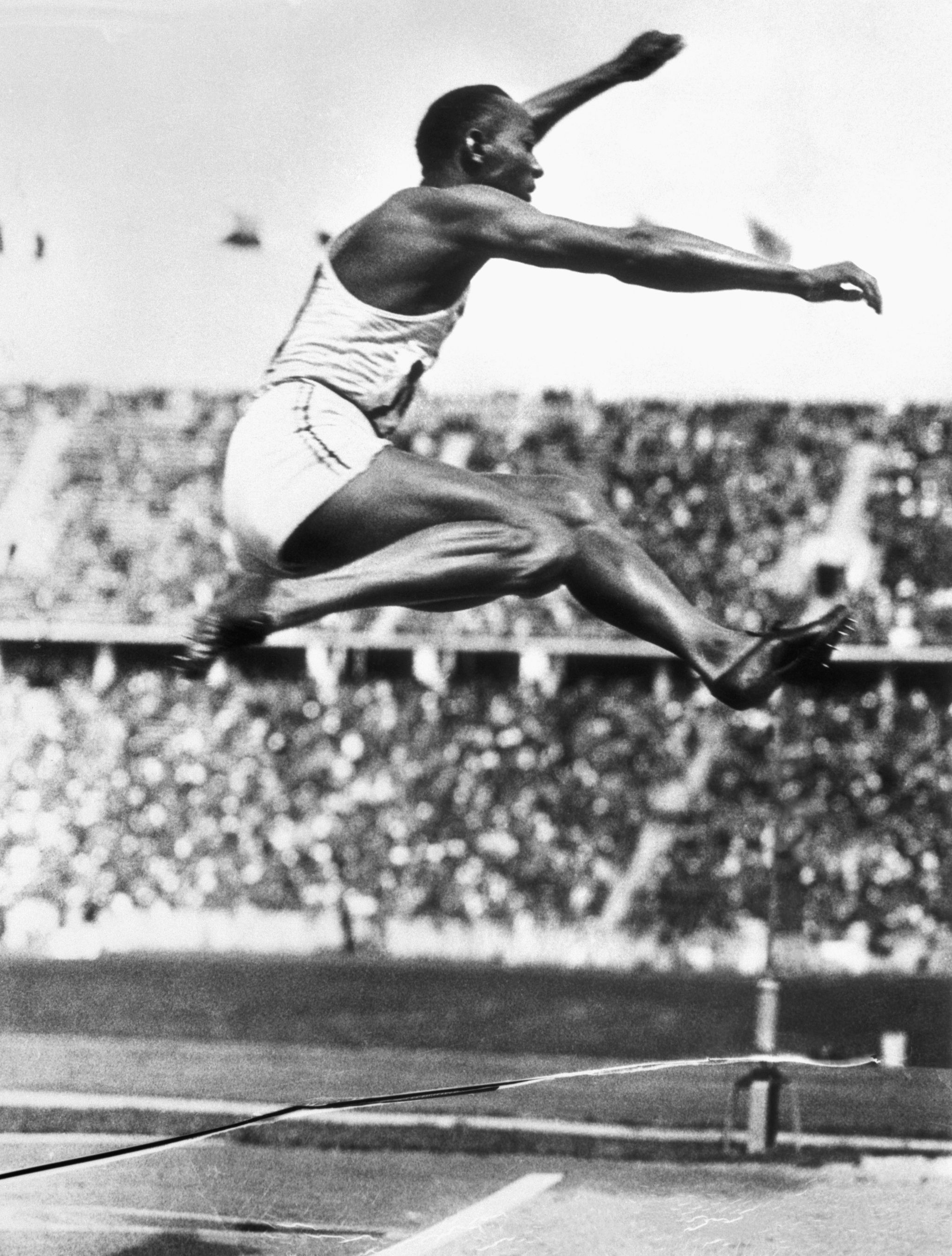

By the time he scooped medal two, for the broad jump (as the long jump was called), he was elated. He wasn’t expecting to meet Germany's Carl Ludwig “Luz” Long, the statuesque European record holder who had set a new Olympic record in the preliminary rounds. “I was told Hitler had kept him under wraps, evidently hoping to win the jump with him,” Owens revealed in 1960. He later admitted that Long intimidated him, so much so, that he fouled on two of his qualifying jumps. But his rival gave him some advice that would cement their future friendship: if he jumped further back from behind the board, he’d avoid a potential foul and still meet the qualifying distance of 7.15 meters (light work for a man who’d set a world record with a 8.13 meters leap the year before). The tip worked and in the final that afternoon, Owens jumped a 7.94 meters that the German couldn’t match. For good measure, Owens smashed Long’s briefly held Olympic record with his third jump, landing a staggering 8.06 meters.

Owen’s third medal should have been his last. In the 200-meter final, he ran 20.7 seconds, annihilating the world record to match “Flying Finn” Paavo Nurmi’s three golds in 1924. But Owens was on a high, and shared with reporters he wanted to run the relay on August 9. The original relay team comprised Marty Glickman, Foy Draper, Sam Stoller and Frank Wykoff. The coaches intended to preserve the best sprinters for the individual events, and give the other runners a chance of medals.

Controversially, Glickman and Stoller were replaced by Owens and Metcalfe. The media speculated the two, who were Jewish, were dropped to appease the Nazi regime. But as African-Americans, Owens and Metcalfe weren’t exactly the favored alternatives. Hitler made no secret of his feelings about black people; in Mein Kampf, he wrote: “The Jews were responsible for bringing Negroes into the Rhineland, with the ultimate idea of bastardising the white race which they hate and thus lowering its cultural and political level so that the Jew might dominate.”

U.S. head coach Lawson Robertson insisted he made the switch not because of anti-Semitism, but because he’d heard the German team would pull out their best runners for the relay. That threat never materialized, however, and in the final, Owens and Metcalfe built a significant lead that helped Wykoff cross the finish line in 39.8 seconds—a world—record time that stood until 1956.

For any athlete, winning four gold medals at a Games was an extraordinary feat, but for Owens, a Black man in Nazi Berlin, it transcended sport, demolishing Hitler’s agenda, which was to showcase his warped ideology of Aryan superiority. Yet considering the runner’s experiences in the United States, it was also deeply and painfully ironic. His Olympic glory did little to diminish the prejudice he faced in his own country, a grim reality he’d faced since his birth in the Deep South.

Born James Cleveland Owens in Oakville, Alabama, in 1913, Jesse knew extreme poverty; he was the last of 10 siblings, the son of sharecroppers, and the grandson of a slave. The emancipation President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed in 1863 to grant slaves freedom in the Confederate States hadn’t translated into economic liberty for the Owens family. In 1922 they relocated to Cleveland, Ohio, as part of the Great Migration, which saw over 6 million African-Americans move from the rural South to the North, Midwest and West, fleeing the harsh Jim Crow laws and the ever-present threat of lynch mobs. Things were more progressive in Ohio, but only just.

Although his strong southern accent caused a teacher to mispronounce his initials as “Jesse,” there was no confusion about his natural running ability. A liberal PE teacher and track and field coach, Charles Riley, noticed the young sprinter and took him under his wing. They trained together daily right through to Owens’s high school years. Several Big Ten U.S. universities attempted to recruit Owens, but segregation hampered his eligibility for a college scholarship. He opted for the best offer at Ohio State University where he could pay his tuition fees by working part-time as a lift operator at the State House, while training and attending classes.

However, he wasn’t allowed to live on campus, and had to share a boarding house with other black students. He was often refused service in local restaurants and couldn’t visit movie theaters. Despite this, he became the first African-American captain of the Ohio State Buckeyes track team, where he earned the nickname “Buckeye Bullet.” He flourished under the tutelage of Larry Snyder, a coach heavily influenced by the heel-and-toe running style used by Paavo Nurmi and the Flying Finns in the 1920s. Snyder particularly wanted to help Owens improve his race starts and broad-jump style. In 1935, their work paid off at what’s been lauded as the greatest 45 minutes in the history of sports. At the Big Ten Intercollegiate Championships in Ann Arbor, Michigan, he set three world records and tied a fourth in less than an hour—with a back injury.

The day would immortalize the 21-year-old in the public eye and, in an ideal world, it would’ve also have changed the way he was treated. Though his reputation grew, he didn’t reap the privileges his popularity should have afforded him, and he faced implicit bias and overt racism. Publications consistently framed him by his race,

This had disturbing parallels with the way traders measured up slaves by their physical attributes at auction blocks in the 19th century.

These theories of black athletic superiority were refuted by Dr. William Montague Cobb, an African-American physical anthropologist who concluded they were unfounded, much like the rationale behind the athletic success of Irish-Americans and the Finns, which also suggested racial superiority. “Industry, training, incentive and outstanding courage, rather than physical characteristics are responsible for the young Negro sprinter’s accomplishments” wrote Cobb. It was also more likely that black competitors were becoming more prominent as the barriers to their participation dropped.

Issues of racial inequality may have stopped Owens from even competing in Berlin, however, as many groups called for the U.S. to boycott the 1936 Olympics. Involvement could be seen as an endorsement of Hitler’s ideology, said Judge Jeremiah Mahoney, president of the Amateur Athletic Union and a devout Irish-American Catholic. Black publications, like New York’s The Amsterdam News, also discouraged Black athletes from taking part, convinced this would support the African-American fight for equality.

Owens, often noted for his gracious personality, wasn’t one for rocking boats. “I wanted no part of politics,” he said of his feelings at the time. “And I wasn’t in Berlin to compete against any one athlete. The purpose of the Olympics, anyway, was to do your best. As I’d learned long ago from Charles Riley, the only victory that counts is the one over yourself.’ He signed a letter along with several other athletes expressing their desire to go – and even when the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) wrote to him to reconsider, he didn’t change his stance.

The efforts made by Avery Brundage, president of the U.S. Olympic Committee, to counter the boycott proved fruitful. Brundage, who was an anti-Semite and admired Hitler, won key votes on the decision at the AAU convention in 1935, which led to Mahoney resigning. But while the boycott bombed, there were merits to the concerns about Berlin. On the first day of the Games, Hitler congratulated the Germans and a Finn who won the first medals, but left the stadium when Cornelius Johnson, an African-American won gold in the high jump. Hitler then declined to meet any winners thereafter. Owens himself pointed to issues closer to home: “When I came back, after all those stories about Hitler and his snub, I came back to my native country, and I could not ride in the front of the bus. I had to go to the back door. I couldn't live where I wanted. Now what's the difference?”

He had a point. Owens didn’t receive a telegram of congratulations or an invitation to the White House from President Franklin D. Roosevelt—unlike the white Olympians. And when invited to a reception held in his honor at the Waldorf Astoria hotel, he had to use the service lift. Still, he hoped the Games would be his ticket to fulfilling the American Dream, as he struggled as an amateur athlete with a young family to support, and wouldn’t get a chance to finish his degree. After the Games he sent out this statement: ‘I am turning professional because, first of all I’m busted and know the difficulties encountered by any member of my race in getting financial security. Secondly, because if I have money, I can help my race and perhaps become like Booker T. Washington.’

Owens subsequently dropped out of a European exhibition tour organized by the IOC and AAU. As a pro, Owens had the chance to follow up on several lucrative offers back in the U.S., including $40,000 (£30,000) to appear with entertainer Eddie Cantor. In today’s money, that would have been life-changing, but the decision led Brundage to suspend him from all amateur athletic competitions, killing his athletic career. ‘This suspension is very unfair,’ Owens told the Chicago Defender. “All we athletes get out of this Olympic business is a view out of a train or airplane window. It gets tiresome. It really does. This track business is becoming one of the biggest rackets in the world. The AAU gets the money. It gets all the money collected in the United States and then comes over to Europe and takes half the proceeds here. A fellow desires something for himself.”

His move into entertainment amounted to nothing, and the offers dried up. He resorted to stunts to make ends meet, racing trains, cars, baseball players and even a race horse in Cuba. “People said it was degrading for an Olympic champion to run against a horse, but what was I supposed to do?” he said later. “I had four gold medals, but you can’t eat four gold medals. There was no television, no big advertising, no endorsements then. Not for a black man, anyway. Things were different then.”

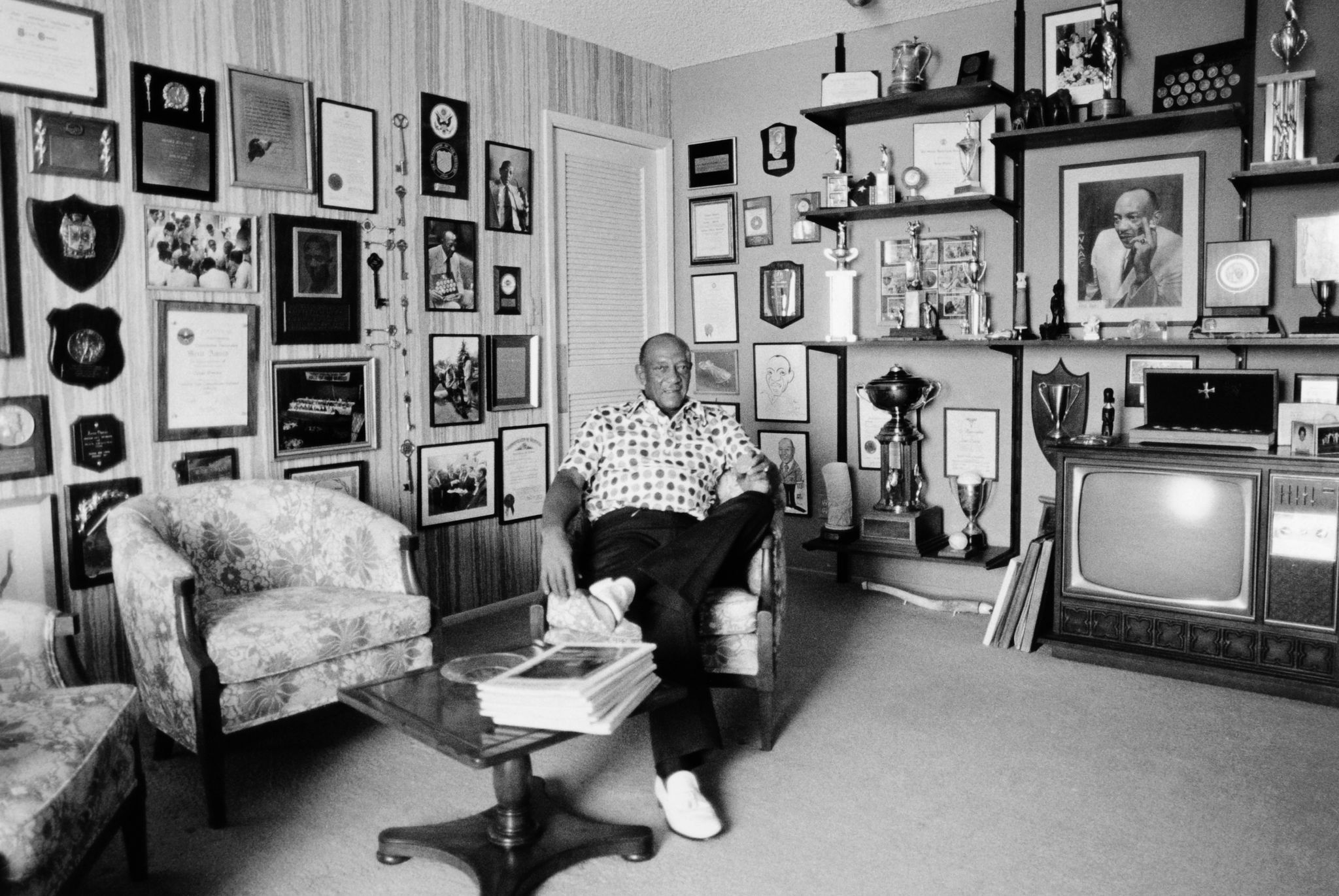

In 1939, Owens filed for bankruptcy when his attempt to launch a chain of dry cleaning businesses failed. He’d take on a variety of roles over the next decade and a half—from heading up fitness and education programs to working at the Ford Motor Company and later setting up his own PR agency. But when President Dwight Eisenhower appointed him a U.S. goodwill ambassador to tour Asia in 1955, his fortunes improved; the well-paid gig lasted right into the 1970s.

While things improved in his personal life, how he perceived himself as a Black man remained puzzling to many. For some time, he appeared to endorse the tenets of respectability politics—the idea that an oppressed group could receive better treatment by behaving in a way that conforms to the dominant standards in society. This became apparent in his 1970 memoir Blackthink: My Life as a Black Man and White Man, where he criticized Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the two athletes suspended for raising their fists on the podium in a Black Power salute at the 1968 Olympic Games. “These kids are imbued with the idea that there’s a great deal of injustice in our nation,” he wrote. “In their own way, they were trying to bring out what is wrong in our country. I told them that the problem certainly belonged in the continental borders of America. This was the wrong battlefield. Their running performances would have done more to alleviate the problem.”

His reprimand would tarnish his reputation in the Black community. Many hailed him as a hero, and expected him, a son of the Jim Crow South, to have stronger views on racism. But in his 1972 book, I Have Changed, he re-evaluated his stance. “I realized now that militancy in the best sense of the word was the only answer where the black man was concerned, that any black man who wasn’t a militant in 1970 was either blind or a coward.”

Jesse Owens spent his life striving to be defined by his merits, not his race. He was a proud American who felt indebted to his country, but he was also a Black man whose extraordinary athletic accomplishments could only take him so far in a country where he was always judged by the color of his skin. But before he died from cancer in 1980, at age of 66, there was some attempt at redress. An honorary doctorate from Ohio State University and an appointment to the U.S. Olympic Committee felt like atonement for the premature end of his athletic prospects in the 1930s. He was also inducted into the National Track and Field Hall of Fame in 1974 and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1976. His long road didn’t pay off with an abundance of wealth, but his legacy as one of the greatest athletes of all time, a man who defied Hitler, remains untouchable.