Six years ago I was a runner who couldn’t run anymore. This happened overnight. One day I ran, the next day I could not. Each time I tried, cramps fierce enough to tear muscle bloomed in my calves after only a few blocks. Even when my legs were at rest, cramps knotted toes, locked up arches. This was baffling. Specialists poked and prodded me. A sports medicine doctor ordered blood drawn and spun. A podiatrist fashioned new orthotics. Each of them shrugged. No one had any idea what was wrong. One guy told me to sleep with a bar of soap beneath my feet, invoking an old wives’ tale. A physical therapist said what I really needed was a sports psychologist to deal with my frustration. I nearly punched him.

I had run since the age of 7. On the day the calves seized up, I was 45. I was no gifted athlete—a few marathons here and there, never a podium finish at any distance, not even the local turkey trot. But speed was never the point. After four decades, running was no longer simply something I did; it was a piece of who I was. I liked the places running took me. I liked the way running made me look—leaner, younger than my age, and more like my father, a runner before me. Mostly I liked the way it made me feel. I had crossed life’s halfway point, and in so many ways was not the man I thought I would be—not as successful, as witty, as well read. But each afternoon when I busted out the door, a low-rent Mercury galumphing around Seattle’s Green Lake at junior varsity speeds, none of that mattered. I was happy.

Without running, my sleep grew fitful. Pants grew tighter. My temper grew shorter. I felt something dark gaining ground in the outside lane, the thing none of us outruns. Nights after work I trudged to the gym with a folder full of stretches and exercises from the many doctors and physical therapists, pieces of a treasure map to a body I feared I’d never see again.

Then one day about three years ago, in the small mountain town of Winthrop, Washington, where I had recently moved, I limped into a log cabin, the office of a physical therapist who came highly recommended. I wasn’t optimistic, but I thought I’d give it one last try. I missed being happy. The therapist, Andrew Nelson, looked me up and down. He watched me move. Then he gave me what no one else in years of searching had given me: hope.

Nelson is 57, with the rangy build of a long-distance runner and sandy hair graying at the ears. He speaks in excited, winding-stair paragraphs that are as likely to invoke sound bites from Eastern religion as the latest article from Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. He’s been a physical therapist for 33 years and a student of running mechanics even longer. He used to jog the streets of downtown Tacoma in college and study the reflection of his gait in the plate-glass windows of department stores. For several years Nelson has run a one-man shop, Altius Physical Therapy, in Winthrop. He has no website.

It was immediately clear to me that Nelson sees the world, and bodies, differently than others do. Even his diagnostic tests are different. First, he told me to march in place as he watched. (I did it, feeling silly.) Next, he told me to balance on one leg, eyes open. (I did it, poorly.) Then he told me to balance with my eyes closed. (I couldn’t do it at all.) He told me to stand up straight while he looked at my posture. He told me to walk across the lobby of the log cabin.

Here’s what he saw: My hips were lopsided and asymmetrical. My pelvis, trunk, and right leg all rotated rightward, and outward from center. My balance was shit. My weight rested on my heels and the outsides of my feet; a tap to the chest sent me staggering backward. Also, I was a toe walker, Nelson pointed out. I pushed off from the front of my foot with every step.

There was more. The gist was that I was a teetering tower—torqued, swaying, unstable, my body’s frame stressed in all the wrong places, with body parts doing work they never evolved to do. Consider those cramping calves: As a toe walker, Nelson pointed out, I propelled myself with my calves and feet with every step I took. But calves and feet aren’t built to power us over long distances, he said.

To Nelson, the mystery cramps that had stymied me and specialists alike for years were no real mystery at all. The cramps were my legs on strike. The legs were weary of moving the way I’d forced them to move, maybe for decades. They’d called it quits.

How could I be so dysfunctional? I’d run four marathons! “We assume just because we’ve been walking all our lives that we actually walk well,” he said later. But no one ever shows us how to walk well. The same is true for running, which is an incredibly complex action, he said. Instead, we bust out the door and never consider whether we’re doing it correctly, in a way our bodies can sustain. No wonder nearly half of runners get injured every year.

Nelson had a hunch how things had gone south. Hips are where many of his patients’ problems begin. Modern humans sit too much, he said. This reduces the mobility of our hip flexors, which in turn limits hip extension—and hip extension is key for runners to get a good follow-through with the legs. Reduced hip mobility can cause a cascade of other problems. What’s tricky is that “the source of the problem oftentimes can be away from the symptoms of the problem,” he said. Imagine a house that has cracks in a second-story room, said Nelson. The source of the problem might be that the wall itself was poorly built. But it’s more likely that the real problem lies far below, in the home’s unstable foundation, he said.

Nelson assured me I would run again. Running isn’t the problem, he said. Running poorly is the problem. “We’re all runners,” he said. “We should be able to run through a lifetime.”

I’d have to retool how I stood, sat, walked—and, of course, ran. It all sounded daunting. Maybe Nelson saw the skepticism in my face. He suggested I embrace a bit of Buddhism, the idea of openness and curiosity called beginner’s mind.

Over the first few visits, Nelson sketched an image of the runner I could become. What surprised me most was all that Future Me wouldn’t do: He wouldn’t bend noticeably at the waist when he ran, and with his lower back aggressively bowed, as if straining for the finishing tape. He wouldn’t propel himself from the rear on exhausted calves and feet. Nor would those feet loiter on the ground through every stride.

The ideal runner he described was barely recognizable. His core and torso stacked stably above hips that were squared up and even. His stride was centered beneath that torso and those hips, and his legs swung evenly to and fro like the pendulum of a clock. Yes, he leaned forward slightly, but his body leaned mostly at the ankles. His footfalls were quick and sure, light even. Each time a foot landed, it pawed the ground slightly, as a stallion scrapes the earth, to set a firm point for what came next. “Ever seen a deer stot, or bounce away from a predator when startled?” Nelson asked one day. Future Me was a stotting deer, planting that front foot, releasing the leg’s stored energy, and bounding off again.

What powered this new runner? Not calves, but glutes—the body’s biggest muscle—and hamstrings, Nelson said, with power channeled through the hips. And every stride would finish with a good follow-through of the leg, in the same way a pitcher follows through with his arm when hucking a fastball.

Efficiency—that was the goal of all of this. A good runner is a stone skipped across water, carrying momentum almost effortlessly from step to step, he liked to say. Other runners are rocks tossed straight up in the air, he said. With every step they lose momentum and must fight to accelerate again. Future Me was a skipping stone.

How to become this runner?

Nelson had an unorthodox prescription. He doesn’t like the gym. He is wary of strength exercises. (Don’t get him started on planks.) In his view, too many of the exercises that runners perform don’t address their underlying problems and can be detrimental. To his mind, once we dial in the correct way to move, all the strength most of us need can come from running itself. (Not everyone agrees with this.) And so, to work on my hip problems and address my asymmetries, my homework was a series of poses.

These included balancing on one leg for minute-long stretches while holding good posture, first with my eyes opened, then closed. In another, I faced a wall about a half stride away and practiced falling toward it, getting more bend from the ankles, while also not breaking at the waist as I fell forward. In a third, I mimicked a flash-frozen running stride: I stood before a mirror and put one foot on a table behind me. The other leg I placed in front of me, as if I were striding. Then I studied my form in the mirror: Were my hips lopsided? Did my lower back bow outward? Did my torso sway backward, or was it stacked and balanced? I made corrections (ideally), and then held the corrected position for 60 seconds. Often I dangled a plumb line from my neck, as Nelson had shown me, to see if my body lined up over the front foot—a stone ready to keep skipping. In still another pose, I leaned forward into a good running position, kept from falling by a climbing harness and thick rubber therapy bands that tethered me to the wall. (That one definitely got looks at the gym.)

I was dubious. All my PT before this had been the “do three-sets-of-10” school of rehab. I knew how to bend to that numbing work. But this was different, more frustrating. My body balked at holding these unfamiliar positions—unfamiliar because they were correct. And I wasn’t used to being correct. As I padded to a new gym with this folder of new exercises, I wondered: Could this possibly do anything? But if these exercises were hard, the only thing harder was contemplating a life without running.

Nelson’s philosophy is that, paired with work like this, thoughtful running “in and of itself becomes your rehabilitation.” He told me I could start running a little bit. It was almost as if I needed that permission—someone to tell me to keep going, that it would be okay. It was hard. The calves barked. I was no bounding deer. But the exercises, and his other tips, quickly had me moving again. After so much time away, I was surprised how difficult it was. It was like running in syrup. I thought, I’ll never again sneer at people who say they hate running.

Still, I was moving. Back in the woods. Back among the flowering balsamroot. About six months after walking into Nelson’s cabin, I ran a 25K trail race in the hills above town, the longest I had run in five years. I was slow and weak, my form a mishmash of old and new. The calves nipped at me. But I did it. In the finish corral I cried.

And the dark thing I’d felt closing in from the outside lane? It was still there at my shoulder. But goddamn if I wouldn’t make him earn it.

Feeling cocksure, I got a coach and a training program and a weight vest, and I trained all summer and fall and into the snowbound winter. I ran and ran. I ran one night when the thermometer read minus 7 degrees Fahrenheit. Nothing stopped me. I might have slacked off a little on the poses. My running form was still shambolic, but: weight vest! I bounced around the gym doing jump squats with 40 pounds strapped to my torso as if it were dynamite. My quads were chiseled.

Nine months after the first race, I toed the starting line at a 50K in Washington’s San Juan Islands, whose course served up roughly 8,500 feet of climbing, while floodwaters sluiced down the trails. It was the biggest day on my feet in my life. I crossed the finish line respectably, in the middle of the pack.

I’m back, I thought, smugly.

I wasn’t, though. Ten days later, not two miles into a shakeout run, the calves locked up, just as they had years before. I hobbled to the car, and limped for days. I tried to run again: no luck. I was confused, humbled, distraught. After all that work, it was as if I hadn’t learned anything at all.

Nelson laughed, but not without kindness. He watched life’s slings and arrows with a “this too shall pass” amusement of the Buddha. Look how far you’ve come in a year, he pointed out.

Truth was, I felt betrayed by my body. Deep down I’d known I was still broken. I still couldn’t do what the poses asked of me. After decades of doing things incorrectly, the flesh felt dumbly disobedient. It was why these bad things happened.

Nelson found my Catholic self-flagellation unproductive. “What is bad?” he asked later, like a good Zen master. “Perhaps bad is also good,” he said. “It’s helpful to have injuries.” An injury is your body telling you that you’ve exceeded its tolerances, he said. Listen to the injury. Learn from it. Then build back stronger. “Beginner’s mind,” he said.

I was no Zen master. But I would try again. I would double down on figuring out my body.

Casting about for inspiration, I read Running Rewired, by the Oregon-based physical therapist Jay Dicharry. Reading the book was as transformational as walking into Nelson’s cabin that first day, and it would prove the perfect complement to Nelson’s tutelage. Though the two therapists use different words—Dicharry’s brief and pithy versus Nelson’s Eastern koans—they agree on many of the problems runners face. Runners usually become injured because they’re not moving optimally and the stresses build, writes Dicharry, who’s also an adjunct professor at Oregon State University and creator of the Mobo Board, a wooden balance board that helps improve stability. If you can steer your joints better, however, the stresses will return to where they belong. “You can totally relearn to do this,” Dicharry told me later. “It’s not rocket science.”

First, he writes, a runner needs to identify what’s stuck or impinged, thus causing this altered movement—often it’s a joint or soft-tissue limitation in the ankle, foot, back, or (ahem) a hip—and get it moving easily again. “Unblock your blocks,” he likes to say. I began daily stretching.

Next comes awareness. Proprioception is the ability to feel where your body is in space. Stand on one leg and assume a running stance. Is your hip externally rotated, or internally rotated? I certainly couldn’t tell. Our proprioception fails us if we’re not intimately familiar with a movement. Without this sense, though, you can’t know whether your body is where it needs to be, or how to steer it. Sharpening it takes practice. Nelson’s biofeedback poses were designed to help me feel what was correct. But I felt unplugged from my body, unable to do even the simplest corrections. I needed to supercharge my sixth sense.

Dicharry’s book was like strength training for my proprioception. With it, I began to lay down crucial new connections so my brain could talk to my hips, back, and legs as it never had before.

Sometimes his exercises were simple—such as sling rows for posture control, in which I simply leaned back from TRX handles, then drew my body upward toward standing while keeping my lower back, torso, and hips in formation. Others looked easy but were grueling, such as the pigeon hip extension: You sit in a sort of raised yoga pigeon pose and then bring your rear knee off the floor by firing the butt muscles. The goal is to grow more accustomed to using the glutes without cheating and using the back, and to begin to rewire the brain to make these new movements second nature.

Dicharry isn’t allergic to strength workouts, nor to people running as they work back from injury; his book incorporates strength regimens. Just as Nelson notes, though, Dicharry says too many runners think they can solve their problems with weight training and by running more miles, instead of by tackling the basic gait and posture issues that made them shaky in the first place. “You can’t put a jet engine on a paper airplane,” he says. “Load the pattern” only after you move better, and can handle it, he says.

I dove in once more—and got a little obsessed. Never a gym rat, I went almost daily last winter and spring, a half hour at a pop. Dicharry’s sayings became my own: “Better booty = better posture.” “Drive from the hips, keep the spine stable.” The more I did the exercises, the more in tune I began to feel with the dull clay of my body, and was able to control it. And something else happened: The more I did Dicharry’s work, the more I could drop into Nelson’s poses and feel when I was wrong, and also how to adjust until I was right. The smallest successes were gratifying—the ability to hold a pose for a minute, the increased limberness of a hip. Success fed curiosity, and hope, and kept me coming back.

And I ran, a bit more every week. Last winter I paired the daily PT with a training program from coach Alison Naney of Cascade Endurance, increasing the distance throughout the spring: 15, 20, eventually 40 miles a week, then more.

Running, though, became almost unbearable. In my head all the habits of a good runner shouted to be heard: Quicken the cadence! Paw the ground! Keep the torso quiet and stacked! Drive from the hips! Be a skipping stone! It was deafening. Every few minutes I had to stop. I was mentally spent. Dicharry’s book put a name to this: the associative phase. It’s when a brain is working hard to establish new patterns of movement, but they’re not yet second nature. I called it misery. (Dicharry tells patients to choose just one concept to work on at a time when they’re on a run.)

“Relax,” Nelson said, as we ran together one day. The goal is wuwei—the Chinese idea of effortless effort, he said. Do you listen to music? he asked. Try it. And let yourself run.

I chugged along fire roads to the Black Keys. Banged up lonesome hills to the Beastie Boys. Bounced down singletrack to Stevie Wonder. Every day I was still Jacob wrestling the angel—a fight for grace. But slowly, slowly, change began to come. By late spring, deep into almost every run, something clicked—an ease where before there had been only struggle, or my body finally understanding one of Nelson’s insights.

On Sunday mornings I choked down oatmeal and headed out for my weekly long run. These Sundays were stress tests of the system, every week a little farther than the last. Every Sunday I was nervous: Is this the day the hard work unravels again? But an hour would go by, then a second. And my body said a grudging yes. Frequently, small new pains surfaced. I would panic. Then I would hear Nelson’s voice in my head: Relax. Keep going. I tweaked my gait until the pains subsided, and kept running. I had a new mantra now: never perfect, but ever better.

Sleep improved. Favorite old pants fit again. I turned the music off, and listened to the bees busy in the lupine, the wind pushing through the ponderosas. And I kept running.

The air was lemony and warm one August day in Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountains when I headed out for a long run. Something felt different. Gone was the feeling of contingency—that it all might collapse at any moment. Descending a pass, I came up fast behind a couple carrying backpacks. The woman startled. “I thought you were a deer,” she said. At the trailhead I flexed my calves. They didn’t cramp even after four hours of moving. Perhaps I was a runner again after all.

These days I think often about my friends who tell me that they, too, used to love to run, but say they’ve been forced to give it up. Their bodies can’t do it anymore. Their voices trail off when they say this, as if remembering an old love.

Could these friends also be runners again, I asked Nelson and Dicharry.

Of course, both replied. Few of us are so damaged that we can’t run once more. But a runner must put in the time, and keep putting in the time, they said. And it requires something else, I know now. “To run throughout a lifetime requires you to always have beginner’s mind,” Nelson told me not long ago. “To always recognize that you are both one stride away from an injury and one stride away from glory.” The journey never ends, until the end.

That used to worry me. It doesn’t anymore.

6 Moves to Rebuild Your Running Form

Most runners aren’t very good at running. We’re stiff. We have terrible posture. To be a strong, injury-free runner, you need to fix imbalances and lack of mobility, and learn how to move correctly, says physical therapist Jay Dicharry.

These six moves, a taste of the program in Dicharry’s book Running Rewired, help improve posture awareness, stability, hip rotation, and flexibility, and will eventually increase power in your stride. Do them twice a week as part of a fuller program, Dicharry says. It’s no quick fix, but it worked for me. You’ve got nothing to lose but your injuries.—C.S.

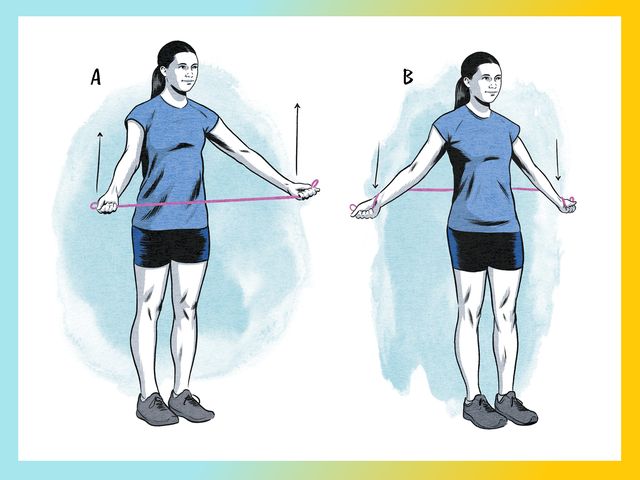

1. BANDED ARM CIRCLES

Stand holding a light resistance band in front of your waist, palms forward with tension on the band (A). Raise arms overhead, elbows locked. Lower the band behind your body, rotating at the shoulders (B). Return to start. That’s one rep; do 20.

2. TWISTED WARRIOR

Get into a lunge with right leg behind you and both hands on floor to the inside of your left foot. Twist your torso to the right and raise your right hand toward the ceiling (A). Hold for a count of one. Repeat to the left (B). That’s one rep; do 5. Repeat with your left leg behind you.

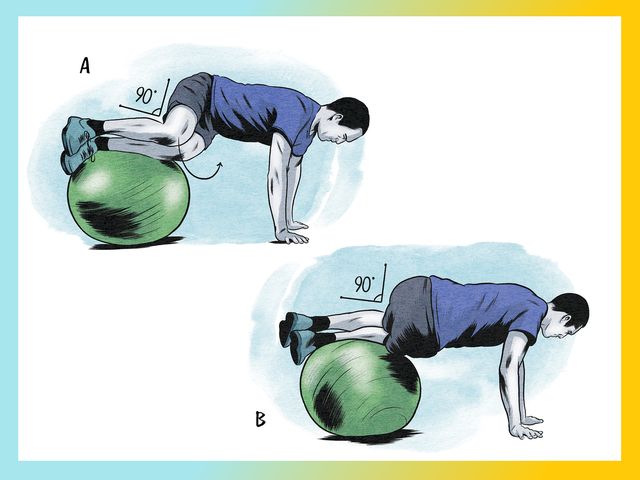

3. SWISS BALL TUCK TWIST

Place your hands on the floor with your shins on a Swiss ball. Bend your knees and hips 90 degrees. Twist at your hips (A) to rotate the ball from left to right in a controlled movement, maintaining the angles as your hips move (B). Continue for 30 seconds. Do three sets, resting for 30 seconds in between.

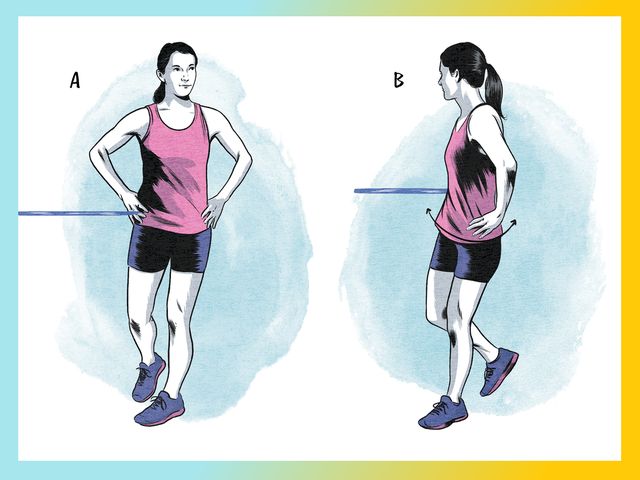

4. BANDED HIP TWIST

Anchor an exercise band to a stable object at waist height. Pull the band behind your pelvis from right to left, and hold it below your waist with some tension on it (A). Stand on your left leg and rotate your pelvis in and out, keeping the band level (B). That’s one rep; do 40 on each side.

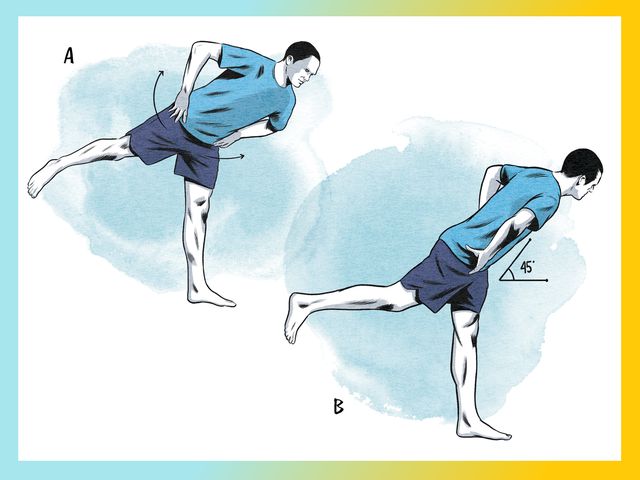

5. TIPPY TWIST

Balance on your left leg, hands on hips. Bend forward 45 degrees, extend your right leg back, and open your hips to the right (A). Twist back in past center and to the left, keeping your weight balanced across your midfoot (B). Return to center. That’s one rep; do 2 sets of 10 on each foot.

6. DUMBBELL PUSH PRESS

Hold a light dumbbell in each hand at your shoulders and stand, right foot forward (A). Bend your knees slightly and explode into a jump, driving the weights overhead. Return to start with left foot forward (B), then repeat. That’s one rep; do 10 on each leg.