The mutt wheezed and shivered, but the salesman didn’t panic. They had run 15 miles together that morning, west toward California. The mutt had chased rabbits and cattle and an antelope, and when the mutt seemed thirsty, the salesman took a gulp from one of the four 20-ounce water bottles he carried and then spit it into the mutt’s mouth.

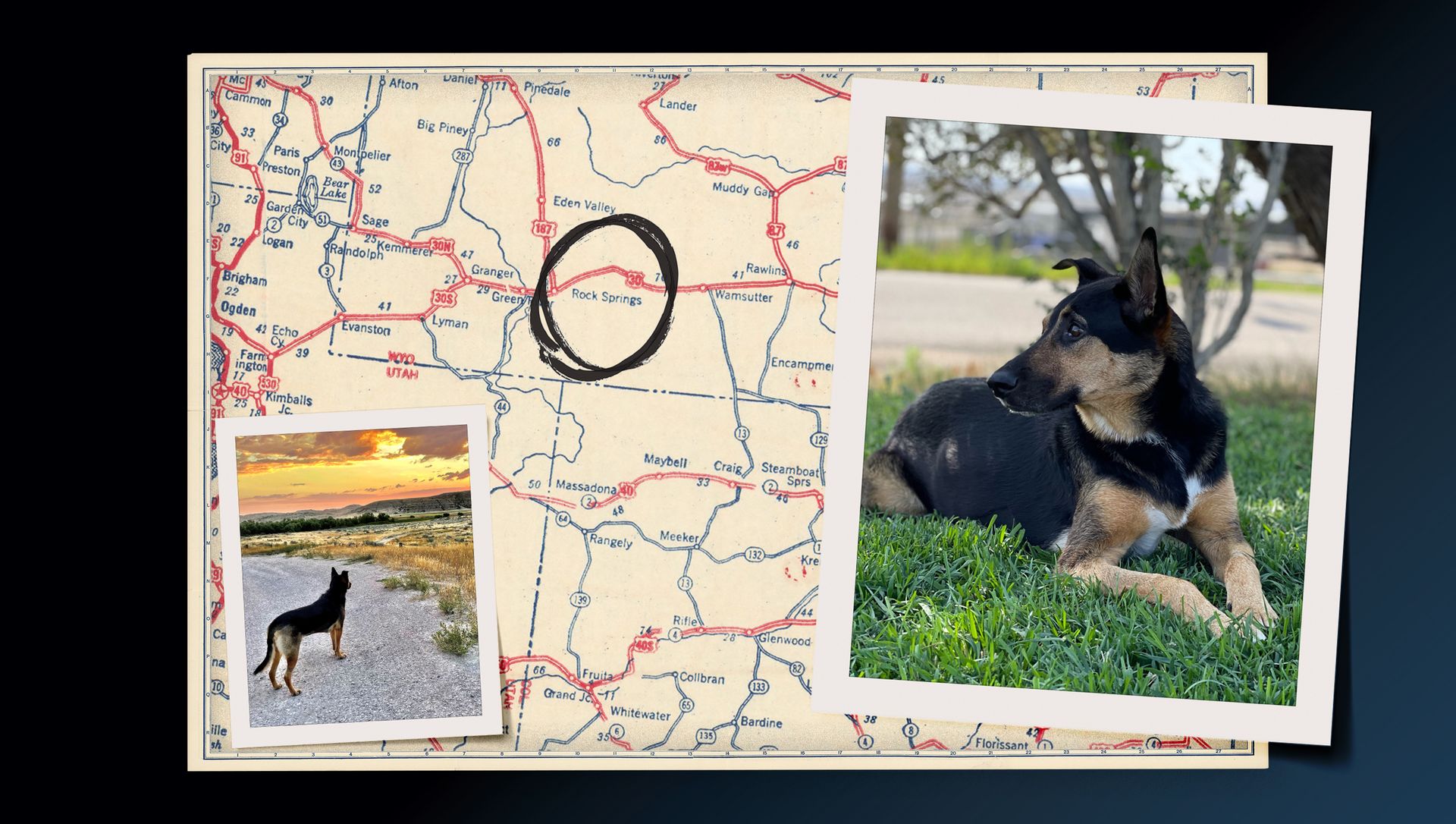

It was 3:45 p.m., Sunday, August 22, 2021, and the salesman and the mutt stood next to a water pump in the high country of Sweetwater County, at the intersection of U.S. 191 and Wyoming Highway 28, outside the front entrance of the larger of the two restaurants in Farson, Wyoming, population 211. The salesman poured cold water from the pump onto the mutt’s broad back, stroked his sides, and felt fur come loose into his hands.

They’d started their journey in Georgia, 78 days and 1,926 miles ago. Watching from 30 feet away, worrying, stood the third member of their party, a chef by profession who handled driving, caring for the mutt, shopping, cooking, gassing up the RV, pulling up the jacks and stabilizing bars every morning, finding water, and dumping sewage. The chef wrote in his journal a lot, about the agony of the settlers who’d lost family members to disease and violence as they traveled this way hundreds of years ago, or the genocide wrought by those settlers on the indigenous people. Everyone who knew the chef spoke of his generosity and compassion, but he did have a tendency to brood.

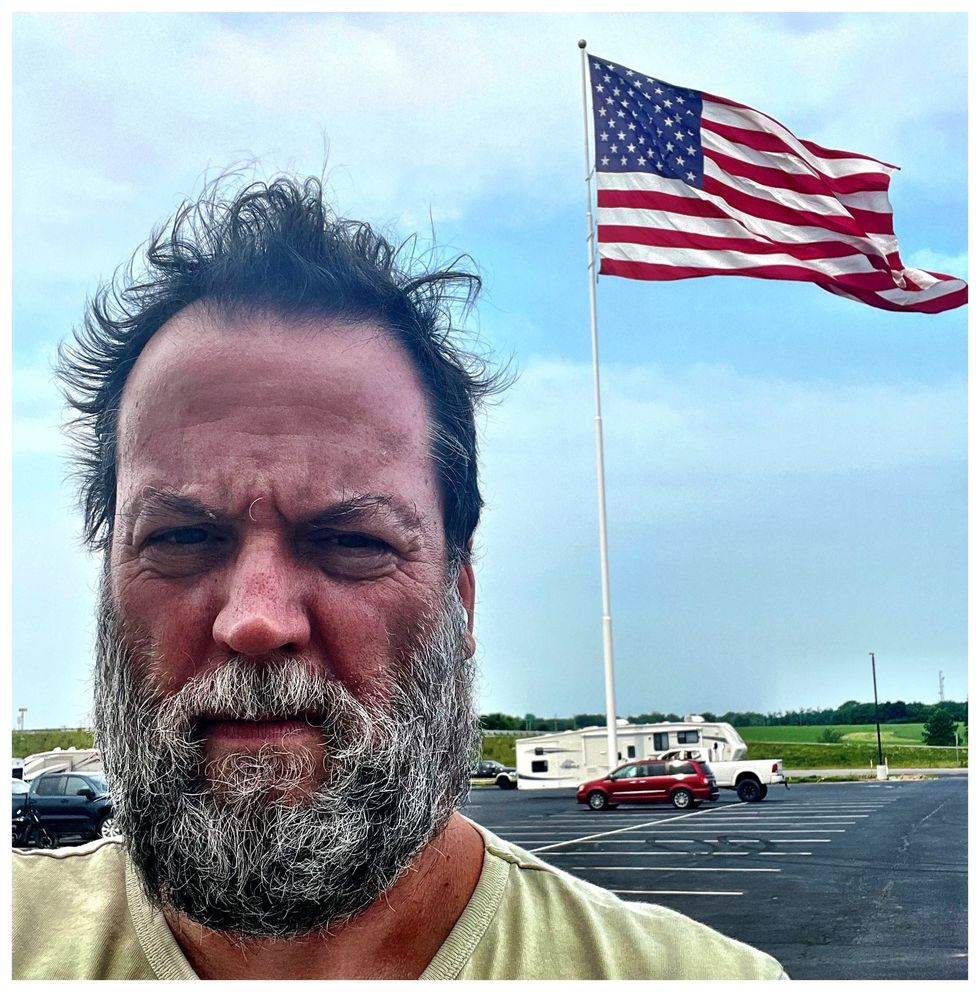

The salesman, whose name is David Green, was 57 years old, an ultrarunner and entrepreneur who owned five companies and had started and sold a dozen others. He lived in Jacksonville, Florida, with his wife of 29 years, Monica, in a 5,000-square-foot house on the Intracoastal Waterway with an enclosed pool.

The chef, whose name is Chris Genoversa, was 59, divorced for 30 years, had been living with his mother in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, and was soon to be homeless. He was a lifelong lover of couches and recliners, a very heavy drinker when he drank, overweight, and so slow on his feet that his childhood friends would invite him on their capers because they knew he—and not they—would be caught.

The dog’s name was Lucky.

After Lucky’s cold-water bath, the mutt seemed tired and didn’t eat. The men reviewed the next day’s route and meeting places (David used an iPad and his phone while Chris depended on a dog-eared road atlas), and then David and Lucky turned in and Chris took a stroll and wrote in his journal.

The chef heard a screeching sound outside his window all night and couldn’t sleep. He was worried about Lucky. Every afternoon, when David left the RV for his second 15-mile run of the day, Chris would hold Lucky and murmur to him until he stopped crying at David’s absence. Chris had grown attached.

The next morning, David woke at 2 a.m., made himself a cup of coffee, and swallowed some fruit and yogurt. Then he held Lucky’s face in his hands. “You wanna go for a run with me? You wanna go for a run?” Lucky barked, as he had every day for the past two and a half months.

Yes.

The mutt and the salesman first met in February 2018, in a Brazilian mountain village called Águas da Prata. David was running the Caminho da Fé, or Path of Faith, a 309-mile route through the rugged Mantiqueira Mountains, with almost 60,000 feet of ascent and descent. The dog was feral, malodorous, and covered with lice and ticks. When David stopped at a posada to rest, the dog stopped but would not enter. David, realizing the dog had probably never been inside a building, carried him across the doorway; then, when David put him in the shower, the dog cried and would not stop until after David soaped, rinsed, and dried him, at which point the dog collapsed, and slept.

When David joined a group of Americans running the trail, the dog joined the group, and when after 24 hours of running David had to stop because of infected blisters, the group, and the dog, continued without him. Only 12 hours later, when David was alone, gazing at stars on a deserted summit, did the dog reappear. When the two finished the trail, a veterinarian told David that if he wanted to take the dog back to the U.S., the dog would need rabies shots; and in his malnourished, mangy state, the shots might kill him. The salesman had found professional success by staying calm, assessing situations, making hard decisions. Left alone, the dog would be homeless, sick, remain feral. At first David called him Rover, but then settled on Lucky Caminho. They had been together more than three years when they stopped in Wyoming. David considered the mutt, with no irony, his best friend.

And now Lucky had cancer. The salesman had known it since they began this journey. But he refused to panic. The salesman had been injured, switched careers, and lost friends to cancer, but with faith and forward motion, things had always worked out.

After running 100 feet, though, Lucky stopped. David walked him back to the RV. He asked Chris if he would mind driving an hour south to Rock Springs. Maybe the veterinarian there could prescribe something for the wheezing, something to stimulate Lucky’s appetite.

Before they separated, the salesman hugged his mutt. “I love you, man,” he said. Then he ran, assessing, planning. Lucky sat in the front seat while Chris drove toward the vet, worrying.

In the summer of 2020, the salesman had told his wife he needed to do something. He was going to buy an RV and run across the country. He would visit his ailing 104-year-old grandmother in California. He would get a firsthand look at the true spirit of the country. He would explore what it means to be an American.

“This is not going to happen,” Monica had said. “Cross-country in the pandemic? No vaccine? It is not going to happen!”

Later that year, when the first vaccine became available, he tried again. What if Monica came along? It would be great! They’d have all that alone time. They’d see the country together. It would be romantic.

Monica’s response: “He said I would drive the RV. I said, ‘Are you fricking crazy?’”

So David asked Monica’s son, 33-year-old Alex, who was 4 when David and Monica married, “Do you want to take part in a grand adventure?” Alex had lost his job when the pandemic began. When Alex agreed, David said, “Okay, let’s go talk to Mom.”

(“He’s a salesperson,” Monica says. “One of the best I know. But he’ll push, push, push. He’s like a teenager who, finally, you just say, ‘okay, stop talking!’” “You get a little crumb,” David says of his sales approach, “and double back again and again.”)

David, Lucky, and Alex left Jacksonville Beach on March 21, 2021, and after a few weeks of 30-mile running days and almost 400 miles, the trip ended prematurely on April 5 when David was diagnosed with a stress fracture in his tibia. Doctors told him he would need to rest for at least three months. Back home, the salesman assessed and planned.

Two weeks later, back in Jacksonville Beach, Lucky started defecating blood and was diagnosed with B-cell lymphoma. He had tumors in his colon and liver. A few days after that, David’s grandmother fell and broke a vertebra and told David she was ready for hospice. (He flew to California to cheer her up. They solved word puzzles together.)

When, in May, David decided he was ready to try again, Alex told him he would need to find a new driver. “Father-son dynamic,” David says. “It can get complicated.”

He called friends, colleagues, former colleagues, competitors from marathons and ultramarathons and Ironman races. Yes, they all agreed, it sounded wonderful. Yes, they all said, it would be great. One person could come out for a few weeks, another person could come out for another few weeks. But this was going to be a great adventure and David wanted someone full-time.

So he called his running coach, Lisa Smith-Batchen, two-time winner of the 135-mile Badwater Ultramarathon, the first American woman to win the 150-mile Marathon des Sables, which crosses the Sahara desert. Lisa had been his coach since 2013. Like many ultrarunners, she considered the spiritual component of the sport to be at least as important as the physical. Unlike many coaches, she eschewed keeping track of time, distance, weight, and other metrics and, at least with David, focused on things like intuition and feelings.

Lisa saw the trip as a vision quest of sorts. She knew how goal-oriented and fond of planning David was, and she was certain he would benefit from something as unpredictable and plan-shattering as a cross-country trip. She also had heard about Lucky and knew the trip would help him pass from life to death and help David learn acceptance.

But she had two children, and her sister had just been diagnosed with cancer. She wanted to join David. But could she be emotionally available to everyone? She told David she would get back to him.

After she hung up, she leaned back in her chair. Her breath slowed. “I prayed about it and meditated about it and, boom…” She picked up the telephone and dialed.

One afternoon in mid-April 2021, the chef sat in his mother’s recliner, staring into space. “I was literally praying for a change of scenery, and I’m not a praying man. But I didn’t know how to change, how to get out of there. Maybe in a week, I would have figured something out. But in that moment, I was like, ‘Show me a sign.’”

At 3 p.m., the phone rang.

It was a woman he’d met at New York City’s Mount Sinai Hospital two years earlier. She had flown in from Wyoming to visit her brother, Steve, who’d had a stroke. Steve was an old friend of Chris’s. She and Chris had spent hours in Steve’s hospital room, sharing stories about him.

She had told him about her ultrarunning exploits, and after she had flown back to Wyoming, they texted occasionally. He told her about his mother, how lost he felt. She suggested he look for work in Jackson Hole, where there were lots of people with money who might want to hire a personal chef.

“Hey, Lisa,” he said. He wondered why she was calling.

“Hey, Chris,” she said. “How would you like to have an adventure this summer?”

Salesman, chef, and mutt climbed into a 31-foot, custom-painted, blue showroom-model Entegra Coach Esteem RV in Murrayville, Georgia, on June 2, 2021. It was seven weeks after doctors had told the salesman he would need at least three months for his leg to heal. The salesman packed the RV with four times as much clothing as he would end up wearing, along with 11 pairs of Altra Torins and one pair of Olympus trail shoes for mountain passes. He also brought compression boots he would never use and a Theragun that would remain uncharged for four months.

As soon as he’d signed on for the adventure, the chef drove to a nearby Walmart in Brooklyn. When he saw that a children’s aluminum baseball bat cost $80, he decided to make the trip weaponless. He did carry a week’s worth of clothes—underwear, socks, T-shirts, a pair of sweats, shorts, and a button-down denim shirt—as well as sneakers, a pair of black New Balance 990s with German custom-made inserts. It all fit in his motorcycle bag. He wore Birkenstocks.

David would wake at 2 a.m. without an alarm and make coffee, and if Chris was awake (the chef sometimes faked sleep when he heard the salesman moving around), David would bring the chef coffee in bed. Then both would eat yogurt, granola, and berries prepared by David. He would run and walk his first 12 to 15 miles in the morning with Lucky. Then, after the chef drove the RV to meet him, they would have “lunch” around 8 a.m. Lucky stayed home for the second 12- to 15-mile run of the day. Dinner was served at 3 or 4 p.m.

The first two weeks, David made his own lunch, usually a sandwich of Brie cheese, raspberry jam, “globs of butter,” and a pickle. But then, professionally disgusted and personally alarmed—David’s weight had plummeted from 172 to 154—the chef took over cooking duties. He prepared lunches of eggs, cheese, avocado, bacon or Jimmy Dean country sausage, and slabs of toast or mounds of grease-soaked tortillas, along with chips and Coke. Surprised and distressed when David didn’t immediately take to the fattening feasts, Chris started grilling the meat at least 10 minutes before the salesman was due back from his first run of the day. The smells did the trick, and David started eating. Later, Chris would wrangle the RV to find David on his midafternoon run and present him with a smoothie, made from ice cream or yogurt and berries and, as David remembers, “crushed macadamia nuts, cashews, almond butter, whatever he found that day—mystery ingredients. They were delicious!”

Dinner ranged from pasta with shrimp to chili to gargantuan salads to panko-crusted cod with grilled portobello mushrooms marinated in olive oil and dusted with garlic. Every night ended with a planning session for the next day, and three-scoop bowls of Breyers vanilla ice cream, topped with frozen Ghirardelli dark chocolate chips. Lucky got to lick David’s bowl.

After David fell asleep, usually before 7 p.m., Chris would leave the RV for a long walk. David thought it was because Chris enjoyed that time of day. Actually it was because the chef was so concerned about David’s welfare that he couldn’t relax until the salesman was inside, safe, fed, and in bed.

Every morning David asked Lucky if he wanted to go for a run, and every morning Lucky barked yes. Every day Chris pulled up jacks and stabilizing bars. The salesman and the mutt trudged through deserts and along muggy river-bottom land. They dodged lightning bolts on mountain passes and stumbled into ditches. Occasionally David ended up running on highways after dark, shrinking away from passing trucks. The chef drove and cooked and shopped and figured out where they would park and sleep at night and made sure the salesman didn’t get lost, or dehydrated, or wind up dead on the river bottoms or mountains and deserts he crossed, or shot on the private land he insisted on traipsing over.

The farther they traveled, the more Chris was impressed at David’s relentless optimism, his refusal to complain, ever, about anything, his athletic endurance and impressive organizational skill, and how he managed, every single week, to find a veterinarian who would see and treat Lucky, often with chemotherapy. It wasn’t easy. David learned that many vets, especially in the South and Midwest, “…were like, ‘You have a dog with cancer? I can lend you a gun.’”

David was impressed at the chef’s easygoing nature, and his cooking, of course, and how kind he was to Lucky. The chef experimented with chicken and various kinds of rice to keep Lucky from losing weight. While Chris drove, Lucky sat in the passenger seat.

On those occasions when David returned to the RV earlier than Chris expected, the salesman could hear the chef on the phone. David assumed the call was to a banker or potential business partners regarding a new restaurant, and he was impressed that an out-of-work chef who was essentially homeless, and with few prospects, was so diligently planning his professional future.

There were differences of opinion, and style, and outlook. David would approach people he encountered and say, “Good morning [or afternoon], this is beautiful country. You’re a fascinating person. I’m running across the country. I’m trying to bring America to Americans.”

As for Chris, “I’m more the baseball bat guy.”

When no one answered after the salesman knocked at a trailer next to a silo near Sedan, Nebraska, David went in and asked the two young men inside sitting in front of plastic bags filled with pills he didn’t recognize, if he and Chris might park the RV nearby to spend the night. (They refused.) When later he described his encounter to Chris, the chef exclaimed, “Are you fucking crazy? Do you want to get us killed?”

David blogged every night, and his musings tended toward the sunny and forward-looking. “The landscape is so grand,” he would write on the 95th day of the journey. “Mountains and fields of cedar, sage, and scrub as far as the eye can see. The vistas unfold each mile, and then a corner is turned into a new panorama.” Even after a day, July 31, when his legs felt so “absolutely dead” that he was forced to walk almost 34 miles, his blogging remained hopeful and bright. “Just because I crashed today, doesn’t mean it will happen tomorrow. And I have the confidence that I will rebound.”

The chef kept a journal, in longhand, only occasionally acquiescing to David’s requests that he be allowed to publish the chef’s writing on the blog. On July 30, the day before David expressed confidence that he would regain his strength, Chris wrote: “The air in Lexington [Nebraska] right now smells like the fertilizer section of Home Depot. It’s not shit, though shit is undoubtedly part of it, it’s further refined, ammonia and other lesser-known commingled contributors to the olfactory clusterfuck.”

And later: “This is backstage of the American dream, where the sausage is actually made. The beef feedlots I’ve now fully experienced are not surprisingly and undeniably a sadistic atrocity.”

They stopped at a barbecue joint in St. Louis and liked the food so much that David bought $100 worth of meat for Chris to freeze. They arrived in Colorado and argued about whether they needed to clean the RV immediately (David) or the next day (Chris). When they couldn’t agree, David started sweeping and mopping and vacuuming and Chris went for a walk. The next day, Chris told David they were a team, and if David was going to make unilateral decisions, the team couldn’t stay together. David apologized, said he understood, promised to be more sensitive.

The salesman ran and planned. The chef cooked and brooded. Lucky ran in the mornings and sat in the RV passenger seat in the afternoons and thought whatever dogs thought.

There were three televisions in the RV, including a flat screen that could be watched outside. None were ever turned on.

Instead, in the minutes and hours when they weren’t running, driving, eating, planning, cooking, writing, shopping, and caring for Lucky, they told each other about themselves.

The salesman learned that the chef took his first restaurant job at a pizzeria when he was 13, and decided he never wanted to do anything else. He loved the sensuality of food in his hands, the social give-and-take with customers. He loved being in charge. (It was a small pizzeria.)

The chef started drinking as a teenager. Then he started drinking more. In the early ’90s, the chef rented a studio in Manhattan’s West Village, and after work, drank. The last decade or so of the 20th century, the chef ended nearly every night (and began most mornings) at Manhattan’s legendary dive, the Corner Bistro. “I could crawl home,” he says.

He tried quitting alcohol a few times, one time lasting six months, once two entire years, but he could never stay quit, until 1999. “No big story,” he says. “It was more like, ‘My god, how long is this going to go on?’”

The salesman learned that he had been wrong in admiring the chef’s hustle and business moxie when he overheard him talking on the phone. Chris had been talking to newcomers in Alcoholics Anonymous, helping them get through the first difficult months and years of their sobriety.

The salesman learned that the chef had opened four restaurants, worked at probably a dozen more. He learned that when the chef’s mother started having trouble getting up the stairs at her home in Brooklyn in 2011, Chris found an apartment they could share “close to her church, which she wanted,” and left his studio and the West Village, where he had lived 20 years. Chris got Covid in late 2020 and recovered. Then his mother got it in January 2021 and died, and Chris thought he had killed her. Before the journey, Chris says, “I was frozen… I wasn’t living. I couldn’t imagine what my life was going to be like.”

The chef learned that when the salesman was a boy, he’d wanted to be a dentist, because a cousin’s father was a dentist, and that family owned a second home, “and that seemed like the good life.” The chef learned that in high school, the salesman found his version of the chef’s pizzeria on a wrestling mat, where—“alone, no equipment, and no one out there and you’ve got to make something happen.” That the salesman switched his major at Columbia University from pre-med to computer science in 1982, the year IBM introduced its first personal computer, and started coding. He learned that the salesman studied what would become his lifetime craft while listening to one of his clients in the garment district as that man called customers in Kansas, in the Middle East, in Asia, “being a different person for each one of them.” That the salesman left coding and took a job as a broker on Wall Street, and then started a company that provided investors with market research.

The chef learned that the salesman ran his first marathon in 1981, that he lived large, that he flew on a whim to Brazil in 1991, right after Christmas, and met a pretty woman at a disco, and that he returned a week later to find her, then sent her a round-trip ticket to New York City, and after her visit, spent $800 a month on long-distance bills until she flew with 3-year-old Alex to the United States to move in with him, and that in March, 1993, they were married and soon thereafter had a son, Gabe.

The chef learned that the salesman sold his market analysis business, then started and sold three more businesses; that he channeled his drive and competitiveness into triathlons, filled with other “high-testosterone, competitive, tech-driven, type-A-type persons”; and that after an Ironman bike crash, he took up ultramarathons and had run 22 of them.

He learned that in 2016, the salesman’s best friend had died of cancer, and that two years later, that man’s son, also a close friend, had died from ALS. He learned how David and Lucky had met, and how much the dog meant to the salesman. He learned that Lisa Smith-Batchen considered Lucky “not a dog, but a special being.” He learned that in the salesman’s view, “Lucky chose me, I didn’t choose him.”

He learned that while the salesman had plenty of money and a loving family, and while he might not have been lost, he was looking for something.

They talked about almost everything, kept only a few secrets. The chef never learned that the salesman harbored doubts and worries about the trip, that he shared those dark feelings with Monica almost every day. “I’m the only person that really knows the David who’s about to cry, who’s exhausted, who’s worried he won’t make it,” she says. “When he calls and tells me that, I say, ‘Well, David, if you’re really tired, you should stop.’ As soon as I say that, he’s like, ‘No, no way, I’m going on.’”

One subject they never discussed: the worst day of the trip, which they knew was coming.

When Chris and Lucky arrived at the veterinarian in Rock Springs, and Chris asked for pills that might help the mutt’s wheezing and appetite, she took x-rays, and told Chris that Lucky’s lungs were filled with fluid, that it was probably the cancer, but might be pneumonia. She outlined options. Chris watched people carrying dogs in diapers, wheezing, in and out of the veterinarian’s office, and thought, “Not for you, buddy,” but he knew it was David’s decision.

David was running in the high desert when the veterinarian called him. She repeated what she had told Chris, and David asked if she could check with some of the other places that had done blood tests, so he could make his best-informed decision. She did, and an hour later called back. It was the cancer.

“That’s what Lucky told me this morning,” David said. “I already knew.”

The chef offered to pick the salesman up so they could return to the veterinarian together, but David demurred. David wanted to remember his final moment hugging the dog. He told the chef that he didn’t have to stick around, but Chris insisted. David asked that before they would meet later that afternoon, Chris get rid of everything that had to do with Lucky—his food, his bed, his bones, the leashes he never wore, his toys, his bowls—everything except for his dog tags.

David spent the next few hours running through the high plains, crying. He came to a bridge by the Platte River and called Monica to tell her what had happened and to cry some more. Because of Chris’s trip to the vet, David was away from shelter, food, and water for hours longer than usual. He tried to move slowly so as not to sweat and lose more water. He was parched and dizzy when a father and son pulled beside him. They had just finished a day of fishing. They asked if he was okay, and he told them he had just lost his best friend. They offered him beer. A few hours later, Chris pulled up. When David entered the RV, emptied of Lucky’s things, “it was like a movie had just switched to black and white.”

They didn’t take a day off after Lucky died, or hold a memorial service. They weren’t those kinds of guys. Lucky wasn’t that kind of dog.

For David, morning runs were lonely and hard. Afternoons seemed longer to Chris. David posted a short blog about Lucky, but otherwise, the big difference pre-Lucky and post-Lucky was that every afternoon, Chris made sure to leave the RV half an hour before David was scheduled to finish his second run. The chef would grab a bottle of water for the salesman and start hiking, so the two men could walk the last mile of each day together and talk. Or not talk.

They took different things from their time with Lucky. “We learned that at a deeper level, animals have to compartmentalize pain,” David says. “So they could survive. It’s been lost on humans, that animal instinct to compartmentalize that pain, to live until you die…”

“Lucky made us into a pack,” Chris says. “Lucky had an influence on us as beings. Your guard goes down. I don’t know if David and I sat next to each other at a bar, we’d ever have a conversation. But Lucky made us into something.”

The salesman still planned and the chef still worried and they still shared dinner and vanilla ice cream with chocolate chips. David still blogged and Chris still wrote in his journal, but sometimes—maybe it was Lucky’s absence, maybe it was just the inevitable sum of an equation involving two men, nearly 3,000 miles, and one RV—tempers flared.

In Eureka, Nevada, David had just finished his afternoon 15 miles. The route had taken longer than anticipated, and he had swallowed his last gulp of the 100 ounces of water he carried two hours earlier. It was 3 p.m. When David arrived at the RV, Chris appeared in the doorway and said he had some bad news. In a rush to arrive at their agreed-upon meeting spot in time, he had driven over a curb and whacked the lowest step on the passenger side. David asked the chef if he had tried to fix it. No, Chris replied, he had not. They didn’t have to drive anywhere until the next day, and Chris was busy making soup, with chunks of brisket and burnt ends and short ribs, from the St. Louis meat, covered with mounds of cheese. The step would be taken care of tomorrow.

David insisted that the step needed to be fixed immediately. He said if it weren’t fixed, the trip was doomed. Chris told him to forget the step and get in the RV.

David fell to his hands and knees, grabbed the step, and tried to bend it. He was slurring his words. There were sharp rocks on the ground. Chris could see the salesman was dehydrated, exhausted, and disoriented.

“Stop it, and get the fuck in here!” the chef shouted. “I’m not saying another word until you take a shower and take a nap.”

David remembers it as, “Get the fuck in the RV or I’m going to pick you up and throw you in.’”

David showered and slept. Chris got the step fixed the next day.

Across thousands of miles and 101 days, along the Trail of Tears, Route 66, the Santa Fe Trail, the Mormon Trail, the California Trail, and the Pony Express Trail, the salesman and the chef asked the same questions of themselves that everyone does, consciously or not: What matters? Who am I? Who do I want to be? How do I navigate the distance between those two points?

Seeking—or avoiding—the answers over their lifetimes, one built and sold businesses, married, transformed himself from a wrestler to a rower to a triathlete to an ultrarunner. The other morphed from a pizza maker into a chef and restaurateur, inspired love, drank too much and then stopped. One conceived of an epic journey that would take months, then followed through even after an injury. The other signed on to the trip from the worn golden weave of his late mother’s recliner because he didn’t know what else to do.

Then both men, at the same moment, faced something else. Planning didn’t help this time. Brooding didn’t, either. Nothing would bring back Lucky. So on the morning of August 24, 2021, the salesman and the chef answered other questions—How do I survive loss? How do I grieve?—the only ways they could. The salesman made himself a cup of coffee and some yogurt and fruit and shoveled it down, and then he pushed off into Wyoming’s chilly predawn darkness and ran 15 miles. And while the salesman was running, the chef scrambled some eggs, tore open a package of Jimmy Dean sausage, and wrote a little bit. Then he cooked and prepared to feed his friend.

On September 26, the salesman ran the final 4.4 miles from Mill Valley to Muir Beach. Afterward, he visited his grandmother (who died seven months later, in April 2022, a month shy of 105), then flew back to Florida and started planning: another ultra in Brazil, the same event that had brought him Lucky; the 683-mile National Trail in Israel, and Spain’s 500-mile Camino de Santiago de Compostela. He would also like to run across Europe, from Lisbon to Istanbul. He buried Lucky’s ashes underneath a Hamlin orange tree in his backyard, and Lucky’s dog tags sit on his desk. He wants to write a book about Lucky, from Lucky’s point of view.

The chef drove the RV back to Georgia, then flew to Newark and caught an Uber to Brooklyn. Eventually he would move upstate to Woodstock, New York, and rent a house with a swimming hole in the backyard and, after a brief stint working as a private chef for a woman in Southampton and a gig working as a “sober coach” for a man who insisted on paying him, Chris thought about helping a friend who was planning to open a pizza joint. It sounded like fun.

Steve Friedman is a writer based in New York whose work has appeared in The New York Times, the Washington Post, Esquire, GQ, Outside, New York magazine, Bicycling, Runner’s World and many other publications.