Yan Daixiang squinted through dense, freezing fog as she struggled to make out her surroundings. Runners were scattered everywhere—off the trail, in ravines, on the other side of the mountain—dotting the hillside in brightly colored athletic gear. It was hard to tell loose clothing and people apart. People trudged in every direction, struggling against freezing wind and rain. Others huddled around bushes or boulders.

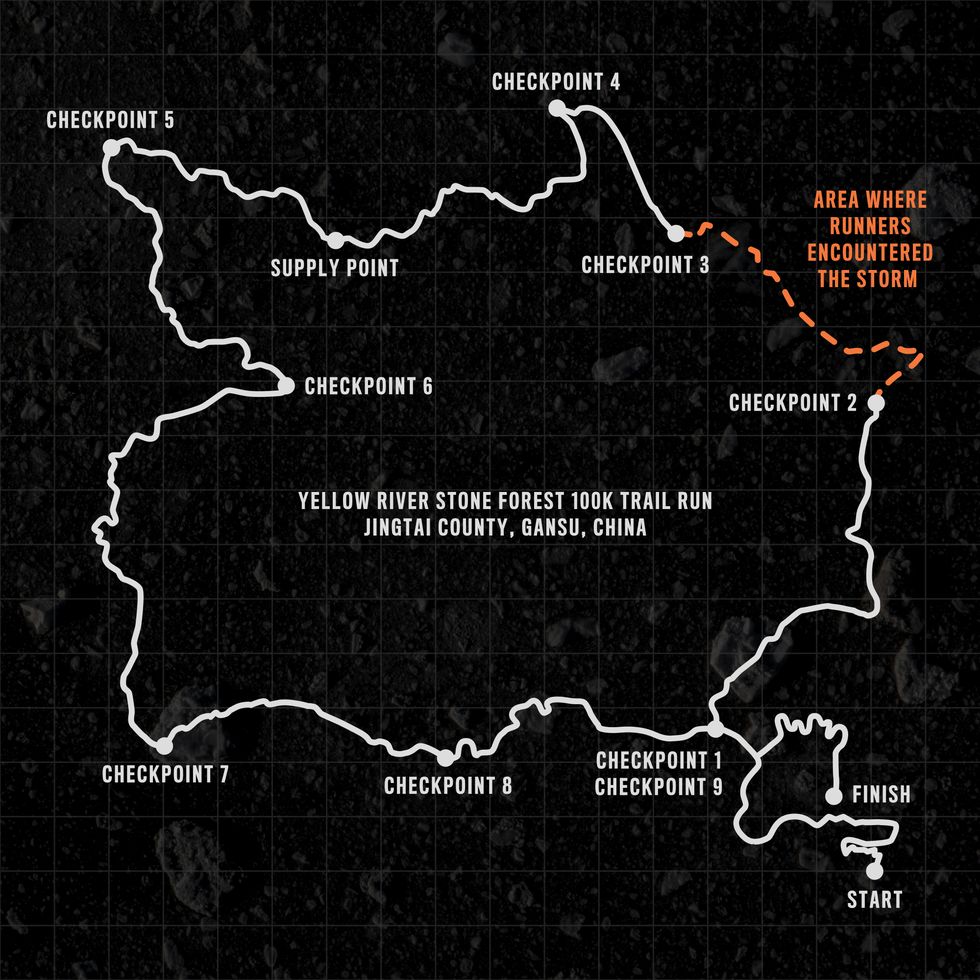

Some runners passed Yan, heading back down the mountain. They’d tried to reach the race’s third checkpoint at mile 17, but failed. They were retreating now, back to the second checkpoint, to drop out.

“It’s way too cold on the top at the third checkpoint,” one cautioned Yan.

The temperature had been dropping consistently since the rain had started. It would get colder the higher she climbed. Yan was still going up.

Most of the runners were wearing shorts and T-shirts. Racers had been encouraged to stow their warm clothes in a drop bag, which they could pick up at mile 39, at the 6th checkpoint. But few had expected they would need extra layers: the Yellow River Stone Forest 100K took place in a desert, and in previous years runners had battled heatstroke, not hypothermia. The bags, if they had anything warm in them, were nearly 20 miles away.

Yan was lucky; she had brought warmer clothes with her. She donned long pants and a jacket, and decided to keep moving.

There was a mile left to climb before the next checkpoint. Around her, more dots of neon color covered the mountainside—crawling, lying on the ground, standing but barely moving. Yan approached an elderly man whose eye was bleeding. He insisted he was fine.

Yan was ascending the race’s most dangerous section: a 2,900-foot climb, which would bring her up to 7,300 feet. The trail led up a mountainside past steep cliffs; the rock and sand of the path had grown slippery now, pounded by wind and rain. There was little vegetation beyond desert scrub to find shelter in. Looking ahead, Yan couldn’t find the trail—the wind had blown the markers away, and fog had shrouded the route. To find her way, she followed a vague pattern among the dispersed runners, like a trend line through a scatter plot.

The path was growing steeper now. Yan bumped into at least three more people, all in shorts. She called out, but her shouts traveled nowhere. She was walking now. The temperature, Yan guessed, was no more than 45 degrees Fahrenheit. Save her chin and forehead, she had covered her entire body. Still, she felt freezing.

The third checkpoint seemed unreachable, and the second was even farther behind her. Terror and dread began rushing in. Yan was pinned.

Yan, 43, had arrived in China’s Jingtai county a day before the race, on May 21st, to sunshine and blue skies. She was excited; she had traveled from her home in the southwestern city Chengdu, a 10-hour drive away, and this was her first time visiting the Gansu Province’s deserts. The landscape was beautiful in a stark, wild way—sheer cliffs rose like sails above the desert floor—and the race, the Yellow River Stone Forest 100K, would be her longest course since China had lifted its coronavirus lockdown.

She’d been running for four years now, starting in 2017, a few years after developing pneumonia. When she returned to work as a nurse at one of China’s largest hospitals after her illness, she found herself weak, freezing, and prone to exhaustion during her shifts.

Running helped her get stronger. She’d begun slowly around Chengdu, but eventually 10Ks and half marathons came easy. Soon, Yan was racing all over China. Between 2017 and 2019, Yan estimated she’d run one 100K ultramarathon each year, three 60K ultras, four marathons, and dozens of halfs. Running also made her a better nurse. She stopped tiring over shifts, and her medical training came in handy during races. Yan monitored herself closely while running, and she often worked as a medical volunteer at competitions.

When lockdown ended in China, in April 2020, Yan returned to running. By the fall, races were being held again, and Yan set off for marathons around the country. A friend recommended the Yellow River Stone Forest 100K, just off the Tibetan Plateau near the Gobi Desert.

The region where the race was held consisted of vast expanses of high desert, filled with rocky sections of mountains and dry washes. Heading into its fourth year, the race climbed rugged hills and mountains above China’s Yellow River, named for its brownish, earthen color. Yan had never seen the Yellow River in such a stark landscape, and the novelty was exciting.

On WeChat, at 8:12 p.m. on the night before the race, Yan posted eight photos—seven of the desert landscape and one of her race supplies. “Conquer the Yellow River, chase the Stone Forest throne,” she wrote. “My goal is to finish the race safely!”

The morning of the race, Yan woke at 6 a.m. to blue skies. Temperatures were in the mid-50s. She threw on long pants, gloves, and arm warmers, and then packed her bag with fuel—electrolyte tablets, energy gels, Snickers bars, and a liter of water. By 7 a.m., the sun was still shining, and wisps of stratus clouds hung in the sky. Temperatures were hovering just under 60 degrees. For sun protection, she wore a bandana around her neck and a sun hat, its large brim and side flaps protecting her cheeks.

On the shuttle bus to the starting line, at about 5,000 feet, Yan snapped more photos of the desert. The sky was still clear. But by the time Yan arrived in the park, wind gusts had grown strong enough to blow over signs and race flags. She lined up for the start, alongside 171 other runners.

The mayor of Baiyin, the nearest town to the start, shot off the starting pistol at 9 a.m. The course began down a stone road, and then bent around a 90-degree turn into a valley. There, runners were hit with an enormous gust of wind. Hats and sunglasses flew everywhere. Yan’s visor flew off, and her hat’s flaps whipped around violently. She chased down her shades and hat and adjusted, and then kept going.

At the front of the race, Zhang Xiaotao grinned as he hit the turn. He liked cooler weather for running. With his cap grasped tight in his right hand, he charged ahead, following the race leaders. One of China’s best ultrarunners, Zhang was competing that day against some other stars in the country’s racing scene—most notably Liang Jing, who had won the 400K Ultra Gobi desert race in 2018 and held the Chinese national 24-hour record.

“When we started at 9 a.m., there were still really big winds, and a lot of people’s hats were blown off,” Zhang later wrote about the race. “But the first 20K were still okay—the situation was relatively normal.”

Zhang had grown up farming in central China’s Henan Province, where he was raised herding goats and harvesting corn by hand. Dashing up and down low, rolling hills of farmland had prepared him well for distance running. By 2014, he was competing in at least 20 marathons a year, bagging top-10 finishes, and sending most of the money he won back to his family. In April, two days after the registration was opened, he signed up for the Yellow River Stone Forest 100K. He was excited. Among China’s landscapes, the dry, open desert of northwest China was his favorite.

In April, to prepare for what he expected to be scalding desert temperatures, he ran during early afternoons, for up to two hours, until he felt hints of heatstroke. By the time the race rolled around, he felt prepared for heat, and he was hoping to finish with prize money. The night before the race, as wind banged at his hotel room windows, he thought little of it. At the race briefing a few hours earlier, the organizing committee had cautioned racers of nothing more than heatstroke and sunburns.

Zhang passed through the second checkpoint, 15 miles in, well ahead of Yan. A few miles behind him, even before the climb, she was beginning to feel the storm’s power. Gusts of wind whipped dirt into her mouth. Hard rain began falling. She slowed down. She stopped to rest for a moment at the second checkpoint. She’d heard that the next checkpoint wouldn’t have any food—just two volunteers punching race cards. Yan decided to fuel up, eating cherry tomatoes, water, and bread. Ahead of her lay the third checkpoint, five miles up the 2,900-foot climb, the race’s most challenging ascent.

The rain was drenching now, and far below her, the river was raging a deep brown yellow. Along its banks, the loess soil was loose and thick. Yan took out her jacket. Her other layers were soaked through, and sand and gravel had filled her shoes. More runners passed. At least half were now ahead of her, starting the climb. Ten minutes later, around 12:00, she set out, head down against the gale.

Meanwhile, the lead runners were barely moving. Wind and freezing rain were pummeling them, slowing their progress to a shuffle. About halfway up to CP3, hail began to mix with the raindrops, slamming into Zhang, numbing his face and blurring his vision.

Zhang had just come across two racers in trouble. One was shaking and trembling, apparently on the verge of hypothermia. Zhang tried helping him forward, wrapping his arms around the runner and walking together. But the trail was too slippery and not wide enough for two people hanging on to each other side-by-side. The wind gusted so hard that they kept falling. Eventually they decided to separate.

Gazing up the mountains ahead of him, Zhang tried to scramble up. Keep your head, get over the mountain, and everything will be fine, he thought to himself.

He didn’t make it far. Wrestling the wind, Zhang fell at least 10 more times. With the two runners he’d tried to help behind him, Zhang was sitting in fourth place—higher and farther into the course than almost anyone. His felt his limbs growing stiff, and hypothermia began settling in as the fog thickened. Soon, he lost control of his body. He fell once more and couldn’t get up. In his last moments of consciousness, he managed to pull out a space blanket and wrap it around his body, and send out an SOS signal on his GPS.

On May 20th, two days before the race, an enormous cold front had pushed down from Siberia to the west of Gansu, where temperatures plummeted close to freezing. The polar vortex was moving southeast, and weather stations in the area began alerting the public. On May 21st, the night before the race—when the race briefing was held—the county’s Meteorological Administration issued a warning that sustained winds between 27 and 32 mph were possible over the next 24 hours, along with large temperature drops possible across the province.

That afternoon, however, temperatures in Jingtai county, where the race was being held, reached almost 80 degrees.

By the race’s start, the edge of the cold front was just starting to descend on the course—perfectly timed to meet runners head-on as they climbed to CP3. Heat and pressure differentials across the front’s edge were causing strong winds, and by 8 a.m., gusts were reaching 25 mph. Temperatures began dropping steadily. But these changes had only just begun at higher elevations; their extremes hadn’t yet moved down into the lower parts of the Yellow River Valley, where the race began.

By 10:30 a.m., an hour and a half after the race started, thick clouds had begun forming as warm, high-pressure air from the desert floor rushed into the sky and cold, low-pressure air from the vortex plummeted down the mountainsides.

The winds and rain grew strongest between CP2 and CP3, as runners climbed higher, into the descending cold front. At this point, as the lead runners were climbing to CP3, temperatures were dropping as much as 7 degrees Fahrenheit per hour. In Jingtai county’s lower elevations— 5,200 feet, about the elevation of Denver—temperatures reached about 44 degrees. But at the race’s higher altitudes, during the climb to CP3, which reached 7,200 feet, temperatures approached freezing. As warm and cold air rushed across the most dramatic pressure and temperature gradients, winds likely reached between 40 and 55 mph. The resulting wind chill made the air temperature at higher elevations feel more like the mid-teens. Together, the temperature, wind, and rain were enough to cause hypothermia, with most runners wearing little more than shorts and a T-shirt.

It is not clear whether race organizers followed the polar vortex, or were aware of the alert, and most forecasts didn’t reflect the severity of the front headed toward Jingtai county. The night before the race, Yan had seen forecasts predicting colder-than-usual temperatures, but nothing especially alarming: in the morning, a light drizzle and wind around 12 to 18 mph, with temperatures ranging from the low 40s to high 60s.

Colder temperatures had never impacted the competition, and most athletes ignored the late change to the forecast, if they even saw it. Yan was one of only a few runners to pack warmer clothes. Most had opted to leave their extra layers at home.

Yan’s cheeks were becoming numb. She was ascending to the third checkpoint and rain lashed the trail, buffeted by gusts of wind. The rock trail was slick as ice, and led perilously close to sheer cliff edges. Visibility was only 15 feet, rendering trail markings invisible, and signs of people had mostly vanished. So when Yan bumped into a runner nicknamed Ke Le, they teamed up, and decided to try to head down the mountain.

“We were just circling ourselves without any sense of direction,” Yan says. Whenever they paused, she could feel her heart racing. Her breathing increased. She started to lose feeling in her feet and hands. She was certain that she was about to freeze to death.

As Yan and Ke Le were trying to descend, they spotted a cave dwelling. The discovery was a deep relief. Among many groups stranded between the second and third checkpoints, there had been rumors circling of caves near CP3.

A shepherd from a nearby village, Zhu Keming, was standing in front of its entrance, beckoning them inside. He was already sheltering another runner, wrapped in blankets and lying on a kang, a bed made of packed earth.

Trembling, Yan sat on the kang and took off her socks and shoes. They were soaked through. “I was like, I’m almost done. I was just too cold,” says Yan. She tucked her feet under the first runner’s hips for warmth and wrapped a dusty space blanket around herself. She asked Zhu to call for help—he already had, and none had arrived. She was sitting close to the other two on the kang, but still trembling.

“I am not gonna make it,” Yan told Zhu. “Is there any chance you can set up a fire?”

Zhu ventured out. About 20 minutes later, he returned with kindling and started a fire next to the kang in the cave. Yan threw her wet clothes close to the flames. Slowly, she began to recover.

Two more runners showed up at around 2:30 p.m., 45 minutes after Yan had reached the cave, and reported that athletes were lying on the ground all over the course. “Almost all of the runners are either in hiding or dropped out,” one of them told Yan. They’d checked some for pulses, often without finding any. Another runner they passed was cramping on the ground, but they couldn’t carry him over.

Zhu went out to look for him. At around 3 p.m., he came back and reported that he’d found the cramping runner, as well as three others who appeared to be dead. The survivor was mumbling, “I’m in fourth place.”

It was Zhang Xiaotao. By then, he’d been lying on the ground for more than two hours. His distress signal had gone unanswered by rescuers.

Zhang could barely move, and Zhu called Ke Le to help carry him inside. To keep the smoke away, they placed him just inside the entrance. Zhang was still dizzy, fixated on the competition.

“I’m in fourth place,” he repeated. “I fell seven or eight times. I want to race.”

With the others’ help, Yan removed Zhang’s wet clothes and placed them near the fire.

She ordered others not to put his hands and feet too close to the flames, or massage his limbs. Yan worried cold blood might circulate to his heart and kill him. She pulled out water, an unopened Snickers bar, and some energy gels. Slowly, Zhang began eating. He couldn’t extend his left hand’s fingers, which were going numb, but he insisted on rejoining the race.

“Mentally, I was still just carrying on in the race,” Zhang recalls of recovering in the cave. Eventually, though, runners calmed him down, and convinced him to drop out. “Then I realized it was a matter of life or death. I was so muddled.”

At around 5 p.m., local villagers arrived at the cave with quilts, thermos bottles, and paper cups, but Yan sent them back outside, to search for runners on the hillsides. A half hour later, the group wrapped towels from the villagers around themselves, and decided to head down the mountain before nightfall. The storm had died down. Thick clouds remained, but it felt much warmer now, and descending wouldn’t be so dangerous. Zhu, the shepherd, led them down a shortcut off the hillsides, following a goat trail.

The trek downhill took over an hour. Along the way, they saw villagers carrying more quilts and hot water uphill. A group of doctors and nurses passed with first-aid kits. A bulldozer followed, clearing a route to deliver medical supplies up the mountain, with all-wheel-drive vehicles behind it.

Yan arrived back at her hotel after 8 p.m. and went to dinner with other runners who had made it back. The meal was somber, filled with speculation about who had survived. Liang Jing, the top ultrarunner, hadn’t been found yet. Others were missing as well.

By the next morning, 18 were confirmed dead. Three were missing. Headlines were spreading worldwide.

Of the 172 runners who set off in the race, 21 died and eight were seriously injured. Most if not all the deaths were from hypothermia. In the lead group of six, only Zhang had survived. Liang Jing’s death was especially unnerving. He was no stranger to extreme races—his win at the Ultra Gobi 400K took place in another corner of the Gansu Desert with extreme temperature fluctuations.

In the postmortem, the race was deconstructed

endlessly. Was the weather a freak event? Should the organizers have been more cautious and prepared? Whose fault was this? That the organizers hadn’t followed the cold front—or had at least dismissed it—was negligent at best. Still, many pointed out there were contingencies in place. Runners were required to have GPS—as well as other bells and whistles one could expect an ultra race to require—and a way to send distress signals. But many of the runners, Zhang and Zhu included, had called for help and never received it. The distress signals had reached rescue teams, but by the time the rescuers arrived, it was too late to save many of the athletes.

Discretion and weather awareness—skills that come with experience—were perhaps in shortest supply. Many wondered why the race committee hadn’t held racers at the second checkpoint. By then, the weather had already turned bad.

The Chinese government’s response to the tragedy lacked nuance. Almost immediately, the government banned ultra races, as well as other “high risk” outdoor adventure sports, the range of which was left vague. The Chinese Communist Party’s disciplinary organ—which, among other things, punishes and investigates officials for corruption—was tasked with looking into the disaster. In the weeks following the race, Jingtai county’s party secretary, Li Zuobi, committed suicide by jumping off a building. He appears to have known what was coming; soon after, a harsh judgment came down from the government’s Party provincial committee, naming almost everyone connected to the race—organizers, sponsors, or others connected to them—as potentially liable.

Around China, race organizers were chilled. So far, 27 officials have been punished or charged, with sentences not yet rendered, while the magistrate of Jingtai County was fired. Other organizers are watching closely, some leaving the industry altogether.

Months later, the runners are still working through trauma and injuries from the storm. Zhang’s left index finger is still numb from nerve damage, preventing him from helping his family with their harvest. He prefers not to talk much about the race’s psychological aftermath. After he published an account of the competition, commenters began harassing him on social media, and Zhang suspended his account. Since then, he’s mostly shut the world out, taking time to heal.

For Yan, the experience has haunted her dreams for months. She has had trouble sleeping—flashbacks to the race woke her up almost every night in the first weeks afterward—but has kept in touch with Zhang and other survivors, for mental support, as well as Zhu Keming, the shepherd. Recently, she’s been mailing him specialty snacks from Chengdu. One day, she hopes, the cave-dwelling crew would reunite at the site of the race to thank Zhu in person.

After the race, Yan and Zhang both took a break from running. Eventually though, they returned. About a month after the tragedy, on a cloudy, cool morning with a gentle breeze, Yan set out on an eight-mile jog in a wetland reserve. The break from exercise made her pace slower than usual, but speed was the last thing on her mind. The reserve was her favorite place to run in Chengdu, and soon the happiness the sport brought her came flooding back. And partly, she explained, she was running for the spirits of the deceased.

“They are no longer running in this world. So no matter what, I’ll keep running, for them and for myself,” Yan says. “I’d dwelled on little details in the past. But eventually, you feel that just being alive is good. Really good.”

Back in his hometown, in Henan, Zhang had taken even less time off. Just 10 days after returning from Gansu, with the blessing of his doctor, he put his running shoes back on. On a bright, 85-degree evening, he donned a white, long-sleeve hoodie, and set out running through the countryside. Three miles later, his life was feeling intact again.

“I’ll carry on, keep running, love everyone beside me, and shoulder their unrealized dreams,” Zhang says. “Ahead, there’s a long, long way

to run.”